The First Days and the Evolution of the Mid-500 Series

In the 1950s and 1960s, Omega was a progressive and dynamic force in Swiss Watch manufacturing and made significant contributions to quality improvement through the design of new manufacturing technologies. The mid-500 series benefited immensely from this eruption of ingenuity, which included such innovations as the Omegametric, a revolutionary system for measuring the torque of balance-springs. Later becoming an important tool for all precision manufactures, it was invented in 1962 by Pierre-Luc Gagnebin.

Marc Colombe created the mid-500 series under the direction of the ageing Henri Gerber who, throughout his long association with the Omega Company, had worked assiduously in continuously improving Omega’s production processes. Along with improved manufacturing came a range of innovations and patents, such as the mobile balance spring stud carrier that facilitated simple adjustments of beat. Invented by Jacques Ziegler in 1959, it still appears in many high-end watches today. These developments underpin the Omega philosophy of employing technology and innovation to improve the performance and volume of its product. The mid-500 series was in many ways a successful fusion of tradition and modernity and the search for an ideal accommodation between quality and quantity, which, today, are often at opposite ends of the scale.

In 1902, Omega was one of the earliest Swiss manufactures to use the divided assembly line, thus allowing quality watches to be mass-produced. Fifty years on in the 1950s, the company underwent a massive growth program that involved takeovers, the development of new production cycles, major construction programs and the expansion of its research and development agenda. A great deal of ingenuity and capital was invested in investigating new horological approaches to old design problems on the one hand, and, on the other, of further automating many of non-critical but labour-intensive functions of the manufacturing process.

Omega clearly demonstrated its cutting edge manufacturing methods in 1960 when 20 thousand Constellations – completed in one continuous production run – achieved chronometer certification with honorary citations for their accuracy.

It was history repeating itself in 1965 when a straight production run of 100 thousand chronometres obtained certification with merit after meeting performance criteria that were double those of movements that met non-merit criteria. These performances were the result of refined manufacturing tolerances that were hitherto unknown in the large-scale production of timepieces.

But, the process of creating an Omega was also high touch in as far as the reliance on human intervention to complete the quality cycle through skilled assembly, hand finishing and expert regulation and adjustment of movements by Omega’s team of ‘regleurs’. Notwithstanding the hype associated with this family of calibres, the consensus amongst informed collectors and horologists is that it has proved over time to be one of, if not the most robust movement series in the history of the Omega Company and of production watchmaking in general. A record quantity of 5.8 million of the mid-500 series of calibres was produced from 1958 to 1969. In the 1960s, Omega Constellations had Rolex on the run, and this is seen no more clearly than in the number of chronometer movements that were certified by Bureaux Officiels de Controle de la Marche des Montres. In 1962, for example, more than half of all certified chronometers manufactured in Switzerland bore the Omega name. Nearly all were powered by mid-500 series calibres.

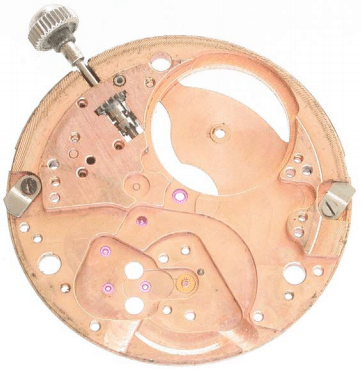

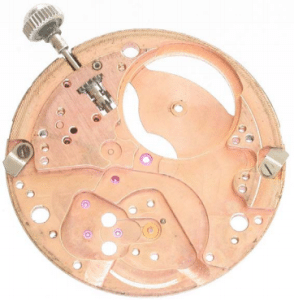

The essential differences between mid-500 series Constellations and the equally famous Rolex Calibre 1570 were in the balance wheel, hairspring and rotor jewels. The Rolex had a white alloy hairspring with a Breguet overcoil, whereas Omega used a flat hairspring made from Beryllium alloy that allowed for adjustments by a micrometer “swan-neck” regulator. The Rolex 1570 rotor bearings were jewelled and the balance wheel featured timing screws. The Omega rotor bearings were made from a bronze alloy.

In critical functional finish there was little if any difference between these two famous calibres, although from a cosmetic perspective many believe the calibre 551 has a subtler and more refined finish than the somewhat over-damascened and colourful Rolex. Omega never gilded the lily in respect to the aesthetics of a movement and the mid-500 series had an elegance and sophistication to its finish that shames its graceless and kitschy successors.