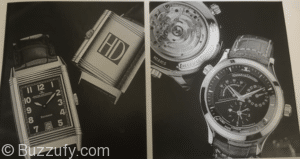

Jaeger-LeCoultre’s famous Reverso watches have been made in a wide variety of movements and cases. For those readers who are not familiar with this design, the movement, in its own case, is held in a frame in the wrist strap which allows the watch to be turned over so that the solid back of the case is presented to the possibly hostile environment. This need arose on the polo field and the ski run and the first model for this potentially damaging usage was produced in 1931. So good was the engineering of the first Reverso case and mount that it remained unchanged until 1985 when a complete re -evalution was made. This resulted in changes as seen in the pictures of the original and of the latest Grand Sport.

While the case mount and frame remained constant, the movement case was and is produced in a wide variety of styles far removed from the original hard working model with its steel back plate. Reverso now appears in gold, silver and platinum as well as stainless steel; in ladies’ styles with lavish application of jewels, in men’s and ladies’ models with Art Deco engraving and/or enamelling, with or without precious stones. A untilitarian design has been transformed into a luxury product. The ultimate mechanical variation appeared, to me, to be the model where the case has two dials, driven from one movement and shows the time in any two selected world time zones!

As one moves through the pristine workshops it is very noticeable that while the components are the product of precise tooling, virtually all the subsequent operations are performed by the manual dexterity of skilled operators (with the aid of such jigs and machinery as needed).

Continually overseeing these work stations are the senior watchmakers ready to advise, help and train. Every part of every watch is put together with a much greater amount of tender loving care than one would expect to find in a modern production shop. I will return to this point later.

While the Reverso production area is fascinating, equally so are the Master Control workshops. Here are designed and made the most intricate of mechanical movements that man has ever produced. It struck me that any other mechanical discipline, if asked to produce so many outputs from a single source, would automatically produce a machine very many times the size of a wrist watch.

In the Master Control world the outputs include second, minute, hour, day, date, month, year, the same information repeated for all alternative time zones, moon phases, chronograph, stopwatch, power reserve, and many other specialized functions made available in the different models.

This complicated and miniaturized machine has to be provided with controls to set it up and to perform its functions when used by an owner who knows nothing about the machine itself. This in itself is a terrific challenge particularly as these controls have been more or less standardized for a long time and the new customer expects the controlls to look and operate in the usual way.

The single source is, of course, the timekeeper beating at 28,800bph. This “heart” is itself the subject of conflicting need as its performance will be the better the larger it is but the larger it is less the room for all the other output train parts. In some models to enhance the consistency of performance in all positions the use of a tourbillon takes up more space. The watchmakers are always ready to show off these ultimate timekeepers to any visitor who asks and I couldn’t resist both times I was there. To see the balance swinging away at 28,800 bph and the tourbillon carriage incrementing around the centre is to see one of the most beautiful mechanisms devised by man – added to that all the parts are glistening with a flawless high finish.

Further space is taken up in a lot of the Master Control watches by the oscillating weight which keeps the self-winding version of the watch wound up by the normal movements of the wearer’s wrist. To satisfy all these demands for space within the normal size and thickness of an acceptable wrist watch taxes the skills of the master watchmakers to the limit and each new calibre is a triumph of knowledge, skill and ingenuity.

Grand Complication

Before turning to part production and testing maybe this is the right point to insert a comment on the way that a unique Grand Complication gets to see the light of day. Firstly a design team in Jean Claude Meylan’s department, led by a master watchmaker, receives a enquiry from within the world wide distribution network. After a great deal of work and testing, the team produce a movement calibre that may fit an existing case or may need a new case. At that stage this prototype is submitted to Eric Coudray. He will spend weeks and maybe longer trying, testing and asking questions before he releases the model for production.

That is a big step for a new design.

After the models are produced and tested they then again each go to a master watchmaker for individual approval for release in J-LeC’s name. The rather special watch which eventually reaches the customer is the result approval of at least three of the top line watchmakers. Personal approval outweighs everything.

Cases

The average customer sees little of the movement but the case is in front of him/her all the time; its successful production is vital to a successful line. At LeSentier there is of course a separate and large case making department. The number of basically different cases is not great, being approximately in line with the number of calibres, but their detailed differences are legion. Different metals – stainless steel, silver, gold, of different colours and carats, and platinum, all require different forming and shaping methods even if the end shape is to be the same. The popular stainless steel is a particularly awkward material.

In additional the settings for the many different jewelling designs have to be provided within the case shape. If part of the case is to be enamelled then the surface must be prepared to the satisfaction of the painter. So the case making design and manufacturing department must be highly flexible and the planning is a production engineer’s headache.

Case design is under the control of master jewellers and smiths in precious metals. Again one sees in each room the experts playing great attention to design detail. In the production department there are precision machines where the product is turned out to very fine tolerances. It is interesting to look dispassionately at a gold case for a Grand Complication. It is made of a relatively soft metal. It is thin by any mechanical standards. It has to snap shut with a satisfying sound. It has to stay shut through much handling, and then has to open easily when required. It must not distort under relatively rough handling. In any field all this would be a major challenge for a mechanical designer! But we can see the successful results at LeSentier all around us.

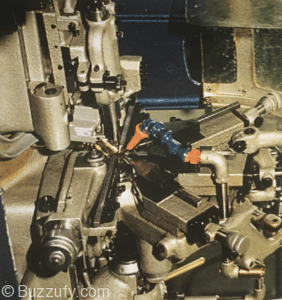

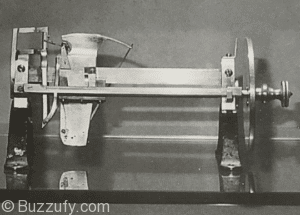

In this account I have emphasized the personal involvement of many skilled people in the completion of each watch but this is all in the assembly stages. Prior to that the piece parts are turned out in the quantity required for a model-run by a range of high quality production machines like punch presses, lathes, mills, automatic capstan lathes. The number of press tools required is very large and each a marvel of precision. The tools and the presses are physically large for it is only in this way that accuracies to hundredths of a millimetre are achieved. Big machines with high rigidity, produce small parts with great accuracy.

Having been employed for part of my working life as a production engineer, I found these complicated automatic machines and their tooling fascinating. They are well worth a separate article in themselves.

Checking and Testing

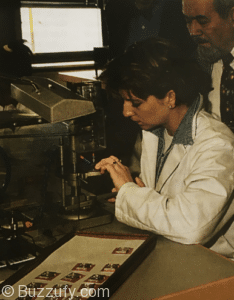

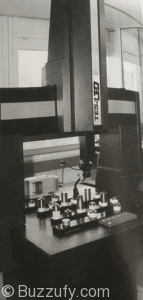

This is a field all on its own. If one makes things to the nearest centimetre then one must measure it to the nearest millimetre. Similarly if parts are made to hundredths of a milimetre then the measuring equipment must be capable of discriminating to a thousandth of a millimetre.

The part measuring equipment at LeSentier exceeds these requirements. Just one example will suffice. This Swiss machine to measure the parts of the Reverso case was obtained, of all places, from Toyota in Japan. It was originally developed to measure car parts. Again the same principle applies as to the press tools; the higher the accuracy required the heavier the machine.

Again, in the final testing, great care is taken to weed out any items that do not meet the stringent requirements. The Master Control watches, for example, are placed in a test rig that rotates them in all planes for 1000 hours with the speed and direction of rotation such that any self winding watch has to wind itself properly or it will stop for lack of power. Similarly any susceptibility to position error is detected by automated timing machines.