Cutting edge doesn’t even begin to describe Rolex, and yet traditional is only the tip of the iceberg. To fully understand the world’s best loved watch company, one must embark on a journey discover the Way – the Rolex Way.

It is very hard not to be impressed, indeed to be awed, by Rolex. The sheer magnitude of its operations, the mere utterance of its name, the very sight of its insignia, the striking aura of its products, the success of its endeavours, and the pride of its people…

Rolex is in a league of its own. As Andre Heiniger, the company’s CEO from 1962 to 1992, once famously said: “Rolex is not in the watch business. We are in the luxury business.” Perhaps this mindset is what led the company to grow to its present size of four sprawling manufactures and more than 6,000 employees all around the world.

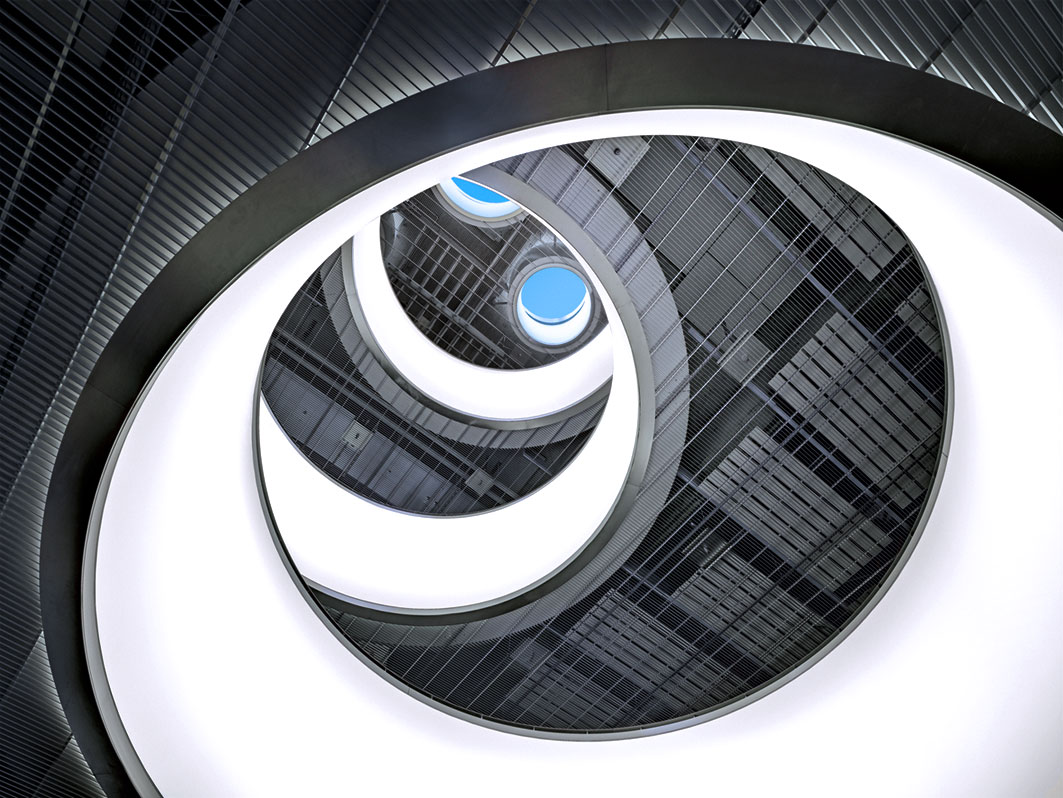

ACACIAS: WHERE EVERYTHING COMES TOGETHER

Of its four sites, the Rolex manufacture in Acacias, a short 10-minute drive from Geneva, is probably the most emblematic of the company because it is the only one that has a facade in the familiar Rolex green. This site, inaugurated in 1965, is now the home of Rolex’s worldwide headquarters and where the final phases of watch production take place. Final assembly, final control, and specialist quality testing are all in a day’s work for the people in this facility.

Possibly the single most impressive thing about Rolex is the unrivalled efficiency with which it produces such outstanding watches. There is none of the customary delusions about everything – every single thing – being in-house or handmade. Steps that are better automated, Rolex automates; those that are better done by human hands, Rolex does by hand. And those which are better outsourced, are outsourced. Approximately 150 people are involved in final assembly work, amid the drone of robots of all shapes and sizes.

Fully tested components arrive daily from the other three manufactures – cases and bracelets from Plan-les-Ouates, dials and gem-set components from Chene-Bourg, and movements from Bienne. At Acacias, they are all assembled over two imposing 10-floor production units in about 10 different operations. It begins from assembly of the dial with the movement, followed by fixing of hands, then encasing, and lastly, final control.

Each and every one of those steps, which precede final control, has been accomplished with multiple carefully homologated procedures that are all geared towards quality consistency. As an example, before hands are fitted onto the movement, the technician first places the movement into a machine specially designed to adjust the gears to exactly before midnight, so that the date of every Rolex watch jumps exactly before midnight. In addition, unlike many watch companies that test only one out of every 50 or 100 watches, Rolex test 100 per cent of its watches.

Along with reliability, performance, and precision, one of the most important values of a Rolex watch is waterproofness – they wouldn’t be called Oysters otherwise. That’s why the water resistance testing at Acacias is a complete system unto itself.

Again, 100 per cent of its watches are tested, and under real-life conditions by submersion in pressurised water tanks. Non-dive watches are tested to more than 10 per cent of their official depth rating while dive watches, in accordance with the ISO 6425 standard, are tested to more than 25 per cent. This is certainly impressive, although not quite as impressive as the waterproof test done on the Rolex Deepsea. This very special watch, certified to 3,900m, is tested to 4,950m in a tank developed for Rolex by none other than COMEX. Each watch also goes through several rounds of precision testing, conducted over a 24-hour period, where robots simulate varius wrist positions. Having survived these brutal tests, Rolex watches can pretty much stand up to anything, which is perhaps the secret formula behind its numerous successful endeavours, from scaling the world’s highest peak to exploring the world’s greatest depths.

PLAN-LES-OUATES: WHERE TIMEKEEPING TAKES SHAPE

The largest of all the Rolex sites, Plan-les-Ouates is a further 20-minute drive from Acacias and comprised six wings, each 65m long by 30m wide and 30m high. It is primarily dedicated to the production of watch cases and bracelets, including the casting of gold and forming of raw materials, as well as machining and polishing of finished components. The Plan-les-Ouates manufacture is also where Rolex produces one of its most extraordinary creations: The one and only Cerachrom bezel.

From its inception in 2005, this facility has been busy stamping, machining, and finishing exterior components like cases, crowns, bezels, and bracelets. Rolex works with a number of different materials to make these components, namely 904L steel (as opposed to the standard steel generally used in watchmaking which is less corrosion-resistant), various types of gold, and 950 platinum. While it secures its stock of steel and platinum externally, Rolex casts its own gold alloys in its own foundry here in Plan-les-Ouates. It is thanks to this highly controlled proprietary process that Rolex was able to create its very own Everose gold alloy in 2008.

Raw materials like 24 gold, copper, silver, platinum, and palladium are first analysed for fineness and inherent quality. In the case of Everose gold, the materials used are gold, copper, and platinum. After these materials are cast together in the foundry, the new alloy is formed into rods and slabs through a series of rolling, drawing, and annealing operations, before being heated again to 1,000 degrees Celsius to stabilise the alloy’s internal molecular structure. This is a crucial step as it softens the rods and slabs for future stamping or machining. When the alloy has cooled, it is sent to the high security vault for storage or used in subsequent production phases.

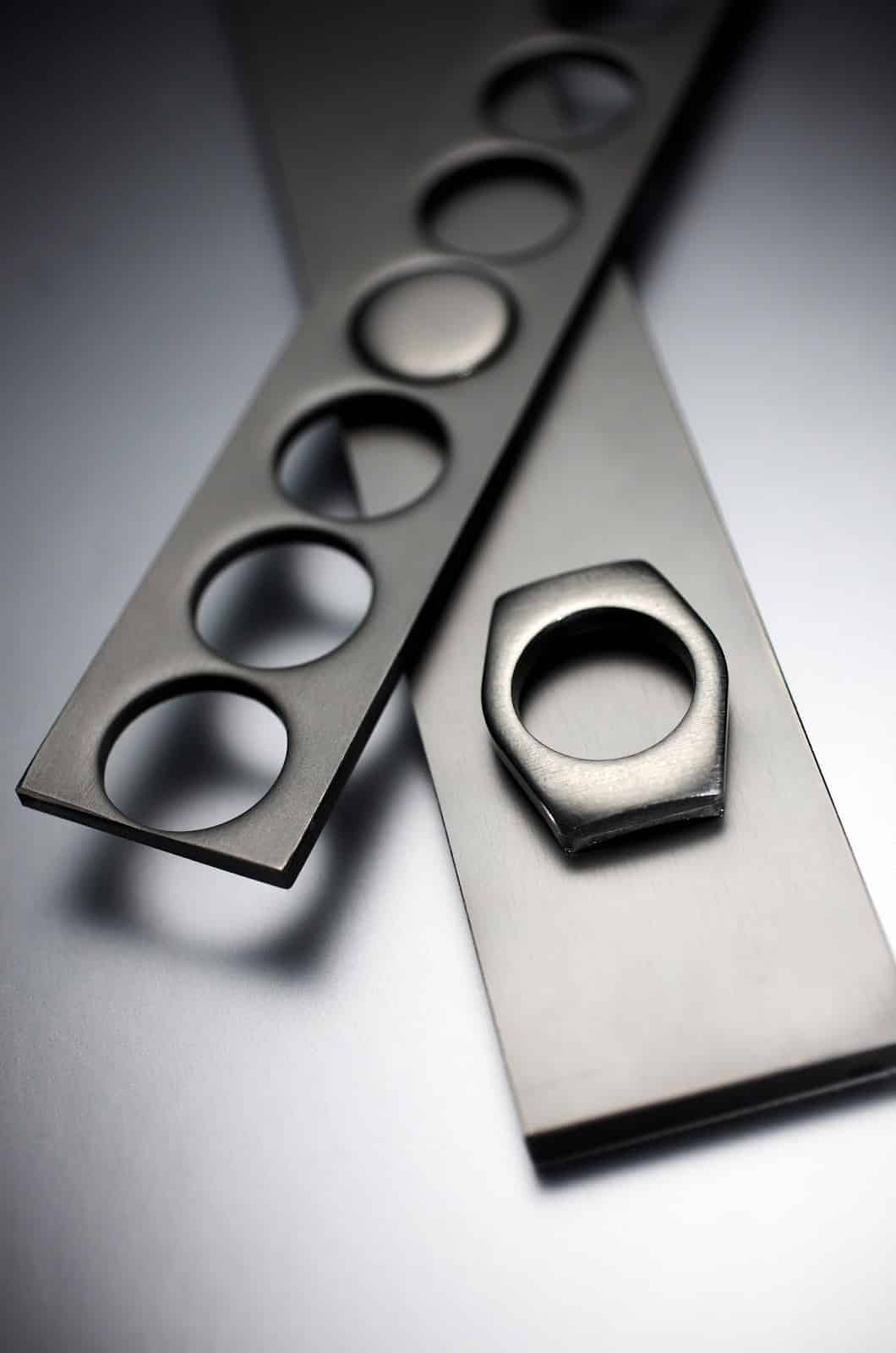

Because of its matchless efficiency, stamping is the optimal method to begin the case manufacturing process. Each Rolex watch consists of a middle case, a case back, a bezel, and a winding crown. All combined there are between 10 and 20 components requiring approximately 150 operations. Blanks for the middle case and case back are first stamped from metal slabs. They are then precision machined to obtain a definitive shape, followed by detailed polishing and satin-finishing. Bracelets, on the other hand, are made up of more than 110 components requiring more than 900 operations, which include machining, assembly by hand, polishing, and satin-finishing.

Every finalised component is sorted into trays, which are barcoded for tracking purposes. These trays then enter an automated stock system devised especially for Rolex. Found in all four manufactures, this high-performance logistical behemoth is one of the key reasons why Rolex is so efficient in producing watches. Stocking and flow of raw materials and components, as well as finished products, are moved from workshop to workshop with minimal losses and next to no down time. This stock area is located underground in the middle of the building, and consists of two 12,000 cubic metre vaults containing a total of 60,000 storage compartments. A network of rails totalling 1.5km spreads throughout the manufacture, like the circulatory system in the human body, sending cargo to individual workshops in under eight minutes.

Of course, it is not possible to discuss Rolex’s Plan-les-Ouates manufacture without touching on its ceramic workshop. Introduced in 2005 in the GMT-Master II Ref. 116718LN, the Rolex bezel with Cerachrom insert has had watch collectors craning their necks for a two-tone one in the classic red-blue Pepsi combination. When Rolex released the GMT-Master II Ref. 116710BLNR with the black-blue Cerachrom bezel, it was obvious that red-blue Cerachrom was in the offing. True enough, Ref. 116710BLRO came along and now everybody wants to know how Rolex did it.

The production of Cerachrom bezel inserts begins with coloured ceramic powder (zirconium oxide), which is combined with a binding agent, and then injection moulded to achieve the shape of the bezel, but about 25 per cent bigger to account for shrinkage that would occur at the sintering stage. At this point, the insert is extremely brittle, so they have to be handled with care. Next, the binding agent is eliminated when the insert is fired to 700 degrees Celsius. This process takes between one and two days as the temperature is increased gradually to avoid micro cracks or bubbling distortion. Then, the insert is sintered to increase its density by bringing the particles of the structure closer together in lieu of the binding agent. As the insert shrinks, its colour also intensifies.

Rolex produces its ground-breaking red-blue Cerachrom bezel insert by using, not zirconium oxide, but high purity alumina which is harder and can be fired at a higher temperature when sintering. In general, to produce two-tone bezel inserts, it is an imperative to first identify which is the dominant colour. In the case of the Ref. 116710BLNR, it is black over blue; in the case of the Ref. 116710BLRO, it is blue over red. The process begins by forging the insert in the weaker colour (red) until before the sintering stage when the dominant colour (blue) is carefully applied over one half. When sintered, the blue will consume the underlying red and eventually half of the red insert will be turned blue.

Next, the entire insert, except for the bezel cavities, is polished using diamond-coated tools and PVD-coated with two microns of gold or platinum. Finally, the precious metal is removed from the external surfaces of the insert but retained in the cavities. Such inimitable mastery of these processes is testment to Rolex’s commitment to quality and performance. The pursuit of perfection continues at its other sites where state-of-the-art machinery is met by longstanding tradition.

CHENE-BOURG: WHERE BEAUTY IS BORN

After final assembly and case construction, the next operations Rolex has mastered in-house are dial production and gem setting. Both of these are done in its third manufacturing facility in Chene-Bourg, just a 20-minute drive east of Geneva. Inaugurated in 2000, this 160-metre-long site has the expertise to produce a staggering array of dials, from the Cellini dials which are either lacquered or embellished with the unique “Rayon flamme de la gloire” guilloche motif to the classical engine-turned Jubilee dials, and also dials made of extraordinary materials like mother-of-pearl, meteorite, gold, or platinum.

Dial making is a traditional operation and Rolex keeps it that way using mostly traditional machinery. Every Rolex dial requires a total of some 60 operations involving both the dial itself and the appliquies, which are always manufactured in 18k yellow, white, or pink gold. Produced mainly in brass, dials are first cut into blanks from strips and then machined to obtain a more definitive form, before they are sent for decoration and colouring. Occasionally, depending on the ultimate design, some dials are machined directly from a solid bar. The broad range of designs offered by Rolex coupled with the sheer number of watches it makes every year (approximately 800,000) suggest that dial manufacture here is on a completely different level than ordinary watch companies.

A large propotion of Rolex dials are chemically treated and there is an entire floor in the manufacture dedicated to this operation. Rolex employs two techniques in electroplating: Physical vapour deposition (PVD) as well as magnetron sputtering. The principle of PVD is where a solid material is heated in a vacuum chamber and sublimates into a gas, which rises and deposits onto the desired surface on the top of the chamber.

Magnetron sputtering, on the other hand, is a plasma coating process where different types of gases interact in a vacuum chamber causing ions of the sublimated gas to bounce all over and get attached to the desired surface in the middle of the chamber. Essentially, the difference between PVD and magnetron sputtering is that magnetron sputtering can apply a thicker coating than PVD. Thus, Rolex uses PVD to apply less than one micron coatings and magnetron sputtering for coatings more than one micron in thickness.

Electroplating, however, is not a simple process in dial making. Rather, it is a lengthy and detailed one that calls for dexterity in handling. After they are cut and machined, the blanks are coated in nickel, gold and silver, before receiving a sun decoration and another layer of gold plating. They are then plated with the final colour as determined by the design department, and receive a final protective varnish. In addition to PVD and magnetron sputtering, dials are also lacquered or coated with transparent varnish to protect from the effects of UV rays, although watch collectors would hardly complain about the beautifully aged “tropical dials” in vintage Rolexes. Still, Rolex aims for perfection.

Once the dials have gone through all the necessary rounds in production, they are matched with hour markers. Strictly applied by hand, each hour marker is welded with one or two “feet”, which are inserted into tiny holes bored into the dial. When all of the markers are properly affixed, the operator sends the dial into a machine that exerts a powerful vertical force on the end of the feet in order to rivet the marker permanently on the dial. A specialist at the end of this production line performs a quality test by dropping the dials at a height of 20cm on a mild surface.

Gem setting is the other major operation at Chene-Bourg. Rolex uses only the most precious stones like diamonds, rubies, sapphires, and emeralds. The in-house gemmology department literally puts each and every stone under the loupe and microscope to determine if it is good enough for its watches. This department possess sophisticated equipment usually found only in independent gemmology laboratories, proving how serious Rolex is in assuring top quality.

Rolex has strict criteria for stones. Only DEFG colour diamonds are used and they are all compared against master stones. Coloured stones are checked against a colour range and they must fall within the minimum and maximum colour acceptable or be returned to the supplier. Stones that have passed the gemmologists’ checks will be sorted and grouped for specific watches. The types of cuts Rolex uses include the classic brilliant cut, the 8/8 cut, the trapeze cut, and the baguette cut, where the 8/8 cut is used only on dials.

Gem setting on dials is another operation that involves a large degree of handcraftsmanship. These dials are machined with cavities meant for the stones but each individual claw or prong needs to be chiselled and rounded by hand. The craftsmen use manual tools to polish the holes, carve out the claws, and secure the stones, all of which must be set at the same height and have their facets oriented in one same direction. This operation alone takes between five days to a week to fully accomplish.

BIENNE: WHERE MOVEMENTS COME TO LIFE

Freshly renovated in 2012, the Rolex site in Bienne is arguably the most sacred of the four, as it is where all of its movements from the fabled Daytona Calibre 4130 to the classic Submariner Calibre 3135 are manufactured and assembled. Its location far away from the other three in Geneva is not without meaning. In the era of Hans Wilsdorf, Rolex obtained large numbers of movements from the manufacture Aegler SA in Bienne and Wilsdorf’s company subsequently came to take over Aegler in the 1930s. The original building still stands proudly with a Rolex insignia on the top but today the movements come from a decidedly more state-of-the-art facility.

Totalling 92,000 square metres, this manufacture is indeed a breath-taking sight. It is here that movement components – from 200 to nearly 400 for the most complex calibre – are stamped, machined, finished, tested, and assembled. Not forgetting that every Rolex movement is chronometer certified, they are all tested by the Swiss Official Chronometer Testing Institute (COSC) for 15 days and nights before being sent to Acacias where they are destined to become fully assembled watches with a case, dial, and bracelet.

Movement components are produced in a similar operation as that of cases and bracelet parts. Coils of raw materials are fed into a machine fitted with a stamp-and-matrix tool that punches out pieces while cutting machines mill pieces from bars and slabs. As a matter of fact, because Rolex also produces its own tools for these operations, many of them are unique to this manufacture. After the pieces are stamped or cut, they are cleaned and then heat treated to 200 degrees Celsius. Efficiency is paramount during these steps and Rolex delivers one finished component approximately every 45 seconds, although there are some components like the main plate of Calibre 4130 which take slightly longer – up to one minute – to produce. Running 24 hours a day seven days a week, the machines are calibrated to plus-minus two microns precision and accommodate between three and five hundred different technical specifications.

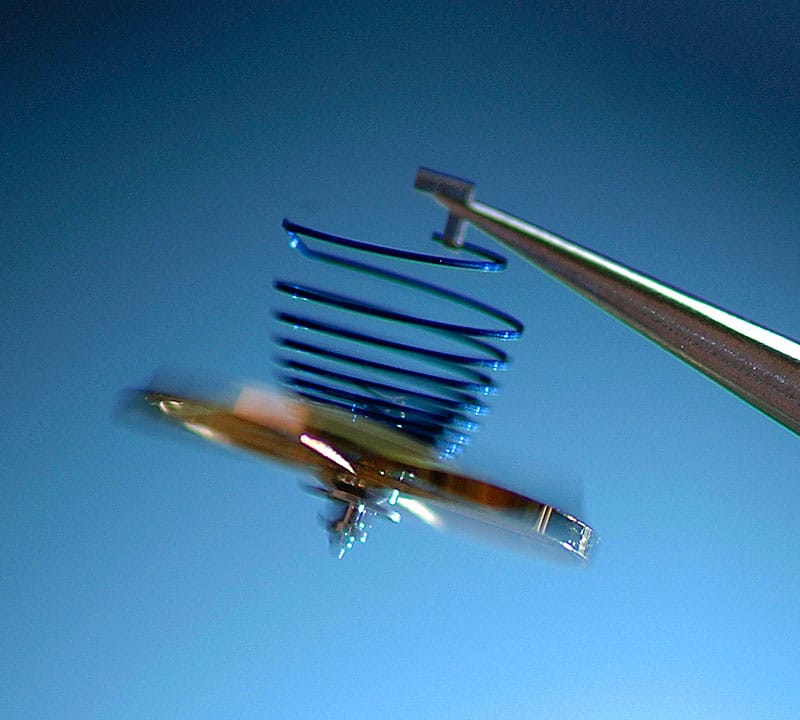

Critical components like the balance wheel, escape wheel, and pallet forks are also produced here. Rolex uses copper beryllium to make its balance wheels and they exist in three dimensions: 10mm for men’s movements, 8 mm for women’s movements, and a special 9mm for Calibre 4130. Since 2000, Rolex has successfully produced its very own balance spring called the Parachrom hairspring. Easily identified due to its rich blue hue, it plays an instrumental role in Rolex’s independence as a watch company.

To produce a Parachrom hairspring, it is essential to first produce the alloy from which it is made. Smelting two bars of niobium with one of zirconium in a vacuum furnace at 2,500 degrees Celsius is the process in a very modest nutshell as, understandably, Rolex does not reveal the exact method for Parachrom. The purity of the material is of utmost importance because at this level of chemistry, even the smallest speck of dust can cause huge problems in the entire batch of the alloy. Once it is successfully produced and cooled, the alloy goes through several stages of laminating and reheating until it flattens from 4.5mm to 1.8mm to 1.5mm to 0.1mm and finally 0.05×0.15 in cross section.

Next is a process involving human hands and expertise: Shaping the hairspring, all 20-something metres of it. The operator coils the pre-cut hairspring into a circular tool, which can accommodate three hairsprings at one time. This is called the estrapadage process, which means to wind springs around barrels. The tools are then placed in a furnace where the hairspring are heated to obtain a “memory” of this shape. After, they are removed and separated into individual hairsprings. Parachrom is not naturally blue; it obtains this distinctive colour from an anodising process. According to Rolex, apart from aesthetic reasons, the manufacture made the decision to anodise the Parachrom hairspring to protect it from the effects of humidity.

When the hairsprings are complete, they need to be fitted with the other components of the oscillator. A technician changes the shape of the hairspring’s inner circle to fit it with the collet, which fixes the hairspring to the axle. Then he cuts the hairspring at the other end and places it in a machine that creates the Breguet overcoil. Pairing hairspring and balance wheel is next, an extremely delicate process performed only by the most experienced watchmakers. This is because each balance wheel has a marginally different moment of inertia and each hairspring, a marginally different level of torque. Rolex has up to 60 different classifications of balance wheels and hairsprings, so pairing which balance wheel to which hairspring would impact the movement’s ultimate precision.

Since 2014, Rolex has also brought a new technical innovation to modern watchmaking – the Syloxi hairspring. Made of silicon, it is the fruit of several years of research and covered by five patents. It offers all of the advantages of silicon coupled with high performance and peerless chronometric qualities. For the moment, its silicon laboratory remains a secret closely guarded from the outside world but Syloxi, along with the other outstanding inventions by Rolex like the Parachrom hairspring, the Paramagnetic escape wheel, and the Paraflex shock absorbers, is proof that Rolex is light-years ahead of the competition. The quest for perfection permeates every single operation in all four of its manufactures; it permeates the mind of every single individual contributing to building these astounding timekeepers. To others, this is science and methodology. To Rolex, this is the Way, the Rolex Way.