For 50 years, to get a Grand Seiko, you had to go to Japan. Not anymore.

Last fall I made back-to-back reporting trips, first to Japan, then to Switzerland. On the Swiss trip, in a meeting with a prominent CEO of a Swiss watch brand, the subject of Japanese watches came up. Unprompted, he declared “Seiko makes the best mechanical watch in the world. I hate to say it, but it’s true.” He was referring to the Grand Seiko, a luxury mechanical watch that Seiko has produced in Japan for 52 years for the Japanese market.

Two days later, in a conversation about my travels with the technical director of another Swiss watch firm, he said, unprompted. “I would love to have a Grand Seiko.”

Behind the scenes and off the record, such heresy is not unheard of in Switzerland. In the Mecca of mechanical watchmaking, one occasionally encounters open admiration for a watch that is a paradox – an expensive, small-batch, chronometer-quality mechanical made by the world’s most famous producer of quartz watches.

In watch circles, Grand Seiko enjoys something akin to cult status. One reason is its exotic Japanese origins: Grand Seikos contain hand-made manufacture movements with Seiko-made components, including hairspring. Another reason is its rarity: Seiko barely makes enough Grand Seikos for Japan and a couple of other Asian markets. But mostly its cult status stems from its performance: Grand Seiko’s claim to fame is that each one must pass a battery of tests more rigorous than Switzerland’s COSC conducts for its official chronometer designation.

Seiko calls the tests, which it performs itself, the Grand Seiko Inspection Standard. Seiko doesn’t overtly claim that Grand Seikos are better than Swiss mechanicals, but it comes close. “The very best of mechanical watchmaking” is how Seiko phrases it. It leaves it to others, such as watch collectors who buy Grand Seikos on visits to Japan and sing their praises on various watch websites, to make the claim for them.

Now foreigners no longer have to trek to the Orient to seek this object of watch-collector fascination. In a dramatic break with a half-century of tradition, Seiko announced in 2010 that it would sell Grand Seiko on 20 global markets. Four models are now available in the United States, ranging in price from $4,400 to $25,000. The latest arrivals are the 130th Anniversary Commemorative Edition, which is a replica of the original Grand Seiko watch of 1960. (The anniversary reference is to the founding of the Seiko firm by Kintaro Hattori in Tokyo in 1881.) The watch features a new hand-wound mechanical movement, Caliber 9S64, and comes in three limited-edition versions: stainless steel (1,300 pieces at $6,500), 18k yellow gold (130 pieces at $16,500) and platinum (130 pieces at $25,000).

The other models are the Grand Seiko Hi-Beat 36000 watch with a new automatic movement with a frequency of 36,000 vph ($7,200); three Grand Seiko Automatics ($4,400 and $5,100); and a Grand Seiko Automatic GMT ($5,500). The decision to distribute Grand Seiko internationally is the latest step in Seiko’s effort over the last decade to elevate the brand’s image by showcasing its ability to make luxury watches in addition to its standard quartz fare. In recent years, Seiko has launched on global markets Kinetic, Spring Drive and even a few mechanical watches priced above $1,000. The arrival of Grand Seiko mechanicals is the piece de resistance in Seiko’s grand brand-elevation plan.

The strategy has its critics, of course. “There is only one thing wrong with Grand Seiko,” the Swiss CEO who so admires it said with a Cheshire-cat smile: “The name!” His point is that for all Grand Seiko’s technical merits, consumers outside of Seiko’s home market will be loath to spend $4,000-plus for a steel mechanical watch (let alone $16,000-plus for a gold one) bearing a brand name they have long associated with mass-produced quartz watches.

That Seiko even makes mechanical watches, let alone chronometer-quality ones, will come as a surprise to many people, who only know it as the brand that launched (in 1969) and led the quartz-watch revolution. But there is far more to Seiko than just quartz. Seiko Watch Corp.’s proudest boast is that the group is the world’s only watch producer to master four timekeeping technologies: quartz, Kinetic, Spring Drive and mechanical. (Two of those, Kinetic and Spring Drive, are exclusive to Seiko.)

In fact, Seiko has a long history as a mechanical watch producer. Today the giant Seiko Group is a totally vertically integrated mechanical watch manufacture. It produces mechanical watches across the price spectrum, from inexpensive, mass-produced, automatic watches called Seiko 5 at the bottom of the price pyramid to Grand Seikos at the top. It makes all the components and movements in-house. Americans are not familiar with the mechanical side of Seiko because, until recently, none were sold here.

Seiko began making mechanical watches, pocketwatches then, in 1895. It has been making mechanical wristwatches longer than most Swiss watch companies. Next year it will celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Laurel, the first wristwatch made in Japan. (For reasons unknown today, Seiko’s custom from the beginning was to give new products English names. “Perhaps Kintaro was already thinking of future export possibilities,” writes Masaharu Nabata in The Seiko Book: The Real History of Seiko Watches.)

Most Swiss watch companies did not begin producing wristwatches until after World War I. The Laurel, Nabata writes, most likely contained components made entirely in-house. By 1913, Seikosha, as the company was called, was making its own balance springs and enamel dials. The first watch to carry the Seiko name was a wristwatch with a small seconds hand at 6 o’clock that debuted in 1924. In 1937, Seiko created a second factory, Daini Seikosha (literally “Second Seikosha”) exclusively for watch production.

World War II crippled Seiko’s watchmaking development. Production shifted to military products during the war; afterward, the Japanese watch industry had trouble rebounding. It wasn’t until 1954 that Seiko achieved its pre-war production level of 100,000 watches per month. In the mid-1950s, however, Seiko went on a crash program to raise its mechanical watchmaking expertise to world-class standards. It was that technical push that led to the creation of the Grand Seiko series.

A turning point in Seiko’s mechanical watch history was the Seiko Marvel of 1956, a 17-jewel manual-wind with an 11.5-ligne movement that represented a quantum leap in accuracy for Japanese watches.

Seiko entered the watch in domestic watch competitions sponsored at the time by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry. The Marvel lived up to its name. It took the top five places and seven of the top 10 in the 1957 competition. In 1958, it took nine of the top 10 sports. The next year Seiko introduced the Gyro Marvel, with an automatic movement containing a major mechanical innovation that is a Seiko exclusive, the Magic Lever. (It’s a device that increased the transfer of power to the mainspring and delivered faster winding speed. It did so by harnessing all the energy created by the rotor as it revolves in both directions. Seiko calls it “one of the key breakthroughs in the modern history of mechanical watchmaking”; it is still used in most Seiko automatics today.) In this period Seiko produced watches like the Cronos and Crown that are prized by Seiko collectors today.

Flush with the success of these products, Seiko felt ready to take on the world champions in mechanical watchmaking, the Swiss. Seiko assembled a team of its top watchmakers on a project to create what they called “an ideal watch.” The goal was to produce the most accurate, durable, legible and easiest-to-wear watch in the world. This was Grand Seiko. Writes Nabata, “All the technicians involved with the development of Grand Seiko knew that their goal was to exceed Swiss chronometer standards. The company set out to make Grand Seiko watches to a standard higher than any timepieces ever made before in Japan; Swiss chronometer standards were the key to this ambition.”

Grand Seiko debuted in Tokyo on Dec. 18, 1960. The original watch had a manual-wind movement, Caliber 3180, with a frequency of 18,000 vph. Its styling was sleek and simple and it carried the designation “chronometer” on the dial. The emphasis was clearly on the movement. Despite a gold-filled case, the watch sold for 25,000 yen, equivalent at the time to two months’ salary of a college-educated professional. Seiko put the watches through a testing regimen more rigorous than that of Switzerland’s COSC. Today, Grand Seikos are tested in more positions, at more temperatures, for more days. After a couple of years, Seiko removed the “chronometer” designation from the dial since the watches were tested at a standard greater than the international standard.

Seiko produced the first generation of Grand Seikos from 1960 to 1975. Seiko itself caused Grand Seiko’s demise: the company’s pioneering advances in quartz watch technology killed demand for mechanical watches. It stopped making Grand Seiko in 1975. By the early 1980s it halted virtually all mechanical watch production.

Miraculously, a decade later, Seiko mechanicals came back, when the trusty tick-tock found new life as a luxury item.

In 1991, Seiko resumed full-scale mechanical-watch production. In 1998, Seiko launched a second generation of mechanical Grand Seiko watches with a new mechanical caliber, the 9S5 series of automatic and hand-wound calibers, reserved exclusively for Grand Seikos. (Seiko had relaunched the Grand Seiko series in 1988, but with quartz movements. To this day, the Grand Seiko line in Japan includes quartz and Spring Drive models.) In 2006, Seiko upped the ante with a new caliber, the 9S6 series, with a 72-hour power reserve.

To find out what makes the Grand Seiko so grand, you travel north out of Tokyo 340 miles to the mountainous Iwate prefecture on Japan’s northeast coast. In the center of the prefecture is the city of Morioka, with majestic views of nearby Mount Iwate. The city of Shizuku-ishi, just outside Morioka, is the home of Morioka Seiko Instruments Inc. MSI is a powerhouse in Seiko Instruments Inc., one of the two giant watch-producing companies in the Seiko Group. (The other is Seiko Epson.) The factory, with 550 employees and 30,000 square meters of floor space, churns out 10 million watches a month. These are the quartz pieces that made Seiko world famous.

Within MSI, however, there is another world.

It’s called the Shizuku-ishi Watch Studio. Here a staff of 60 highly skilled watchmakers and technicians make watches the old-fashioned way. The Watch Studio is a full-fledged manufacture, the only one in Japan. Here, says an MSI executive, “we develop, we design, we manufacture and we assemble luxury mechanical watches.” At spotless workbenches in a large, spotless room, 19 watchmakers manufacture mechanical watches, one by one, by hand. Attached to each watchmaker’s spacious desk (the word “workbench” doesn’t do it justice) is a plaque with the watchmaker’s name in Japanese and English. Each desk is customized for the watchmaker. The lacquered wood desks and cabinets in the studio are Iwayado Tansu, traditional craft furniture that is a specialty of the Iwate region.

The watchmakers make and finish the components, they assemble the movement, and they adjust and regulate it. Using customized tweezers, they adjust the curves of hairsprings, made of an exclusive, Seiko-developed alloy called Spron, which are only 0.03 mm thick. Then technicians test the movement. A lot. The first round is for 300 hours, after which the watchmakers fine-tune the movement again. At that point it is ready for its 400-hour Grand Seiko inspection.

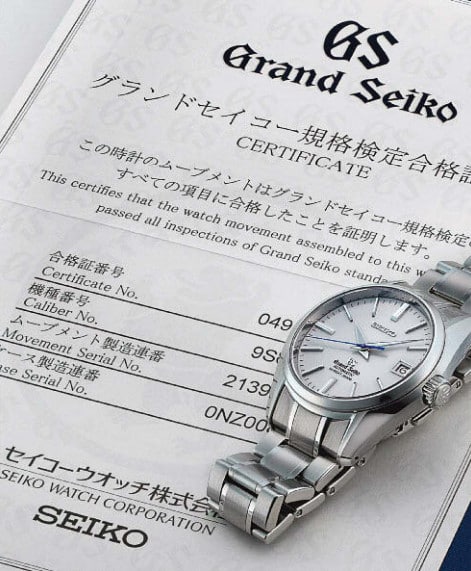

Movements that pass are then assembled by hand into a case that has been hand-polished. Each steel, gold, or platinum case is polished using a special technique called Zaratsu, or blade polishing, which creates a flat, smooth, mirror finish. The complete watch then gets a final inspection. In total, every Grand Seiko watch spends more than 1,000 hours being tested and inspected. Each watch comes with a rating certificate certifying that it has passed the Grand Seiko Inspection Sandard.

The Shizuku-ishi workshop produces more than 20 different mechanical watch calibers in two families, Caliber 68 and Caliber 9S. Caliber 68 is a series of movements used in thin mechanical dress watches that Seiko sells in Japan under the Credor label. Caliber 68 is an ultra-thin, hand-wound movement just 1.98 mm thick. The Caliber 9S series, which Seiko calls “the flagship of Seiko,” is used exclusively in Grand Seiko watches. With all the handiwork involved in the calibers of both families, the manufacture’s annual output is small. How small is a Seiko secret; Japanese sources put the number of Grand Seikos produced per year in the thousands rather than tens of thousands.

Seiko created the Caliber 9S series for the revival of the mechanical Grand Seiko collection in 1998. The first movement, 9S55, was Seiko’s state-of-the-art mechanical movement, an automatic with 50-hour power reserve. But to live up to the Grand Seiko ideal, Seiko felt the watch should run for an entire weekend without winding down. They achieved that in 2006 with a new caliber (the 9S6 series) that runs for 72 hours on a full charge. “The long power reserve of 72 hours relieved a major concern,” says one Morioka Seiko executive. “There is no need to reset the hands on Monday morning, because the watch will continue operating through the weekend.”

Seiko says the improved power reserve is the result of two major advances in component manufacturing at MSI over the past few years. One is the introduction of Micro Electro Mechanical System (MEMS) engineering in parts production. MEMS is a technology developed for the integrated circuit industry that is now being applied to watchmaking. The other involves improvements in Seiko balance springs and mainsprings made with Spron, the highly elastic in-house alloy that Seiko Instruments developed for mainsprings. MSI says Spron, which is a registered trademark of SII, delivers more torque and resistance to shock.

Calibers in the 9S6 series use a longer, wider, and thinner mainspring made of Spron510, an improvement over the Spron200 mainspring in the 9S5 series. Balance springs are made of Spron610, with greater shock-resistance and anti-magnetism (10,000 A/m). The caliber also has a new MEMS-made escape wheel and pallet. Compared to traditional machined parts, MEMS technology produces components that are lighter, more precisely cut and more durable, with smoother surfaces. The result, Seiko says, is greater accuracy.

Seiko uses the same technology in the Grand Seiko Hi-Beat 36000 watch introduced last year. Seiko is one of just two watch firms (the other is Zenith) to manufacture a 10-beat caliber. High-frequency watches have better accuracy because they deliver 50 percent more torque than a standard eight-beat movement. The downside of 10 beats is a low power reserve and low durability. Seiko’s Caliber 9S85, however, manages a power reserve of 55 hours. Like other members of the 9S family, it has a MEMS-manufactured escape wheel and pallet and Spron610 balance spring. The mainspring is made of a new material, Spron530, which SII developed with the Metal Material Laboratory of Tohoku University in Sendai, Japan.

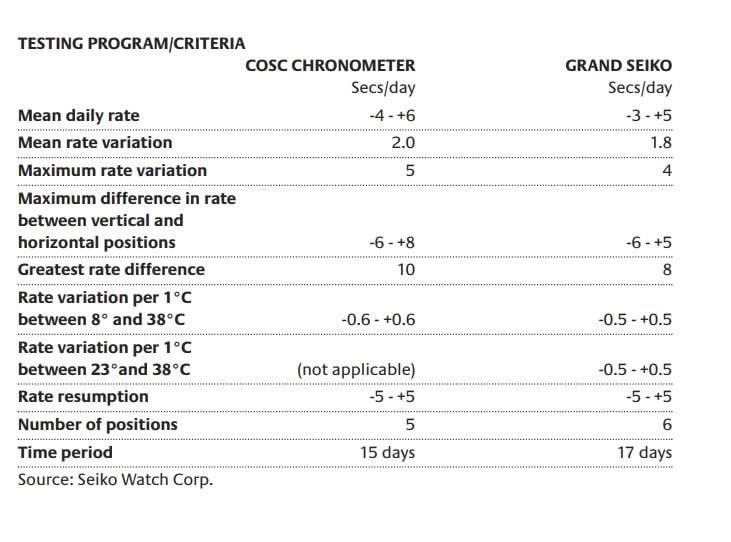

Standard Procedures: Seiko vs. COSC

How does Seiko’s Grand Seiko Inspection Standard differ from the COSC tests required for a Swiss mechanical chronometer? In three ways, Seiko says. “The Grand Seiko standard involves more tests in more positions and at more temperatures than today’s chronometer standard,” Seiko says in a statement.

Here are the differences:

1. Seiko tests its Grand Seiko movements in six positions versus five for COSC. Both Seiko and COSC check the accuracy, or rate, of the movement in various positions simulating the various angles a watch is in when on the wrist. Seiko, however, adds one additional position: the position of the watch when it is not being worn and placed vertically on a flat surface, crown right, with 12 o’clock at the top.

2. Seiko tests Grand Seiko movements with two temperature variations versus COSC’s one. Changes in temperature can affect the performance of a watch. COSC checks the thermal variation of daily rate between 8 and 38 degrees Celsius and requires that the rate variation not exceed +/- 0.6 seconds per day. Like COSC, Seiko checks thermal variation between 8 and 38 degrees Celsius. But Seiko conducts a second test for variations between 23 and 38 degrees Celsius. The extra temperature rating is closer to body temperature. Seiko has a slightly tougher standard than COSC, +/- 0.5 seconds per day.

3. Seiko tests Grand Seiko movements for 17 days versus COSC’s 15. The two extra days are for the test of the movement in the sixth position.

The Grand Seiko standard has been revised several times over the years. The current standard was set in 1998, when Seiko revived the mechanical Grand Seiko collection with the Caliber 9S family of movements.

The following table outlines the differences between the COSC and Grand Seiko standards.