Can you think of a single brand that doesn’t offer a chronograph in their current line-up? The chronograph is still perceived today as one of the most desirable complications a watch can feature. Technically challenging to produce and design, and built for a specific usage (military, aviation, racing), the chronograph is a must-have for any resprectable watch company.

Valjoux 72, El Primero, ETA 7750, Lemania 861, Longines 13ZN: all these calibre references are well-known in the watch industry for powering some of the most famous chronographs out there – vintage Rolex Daytonas, Longines Zenith El Primero, Breitling Chronomat and Omega Speedmasters. But what about the other manufacturers that tried hard and sometimes failed to come up with their own version of what a chronograph should look like, and run like?

Before the era of computer-assisted design and cutting technologies with nanometre precision, designing a calibre from the ground up was a complicated enough task already. However, crafting one with a chronograph function was much more of a hassle, and very expensive to boot. Consequently, few brands took up the challenge of building their own calibres, to try to outsmart the competition. Some succeeded better than others. Here are five worth mentioning.

1. Excelsior Park

This company was founded in 1866, in the small town of Saint-Imier in the Bernese Jura, also known as the birthplace of Longines, Breitling and Heuer. At the end of the 19th century, the company added some modifications to the chronograph calibre invented by Alfred Lugin, the founder of Lemania, which increased its credibility in the marketplace and led to its later becoming one of the leaders in terms of sports timekeepers and chronographs during the first half of the 20th century. Every sport had its own dedicated timer: rugby, water-polo, football, basketball and even boxing.

In 1918, Jeanneret-Brehm et Cie, which had previously produced watches and movements under different names and companies, finally became Excelsior Park. The list of different types of chronographs and sports timekeepers is long, so let’s focus on a specific calibre, developed in 1938: the 12/13, later known as the calibre 4 family. Produced in mono- or double-pusher configurations, the chronograph was sold under the name Excelsior Park but was also supplied to other watch companies such as Gallet & Co, Zenith and Girard-Perregaux. The movement family offered a 30-minute or 40-minute counter, and came with the option of a 12-hour counter.

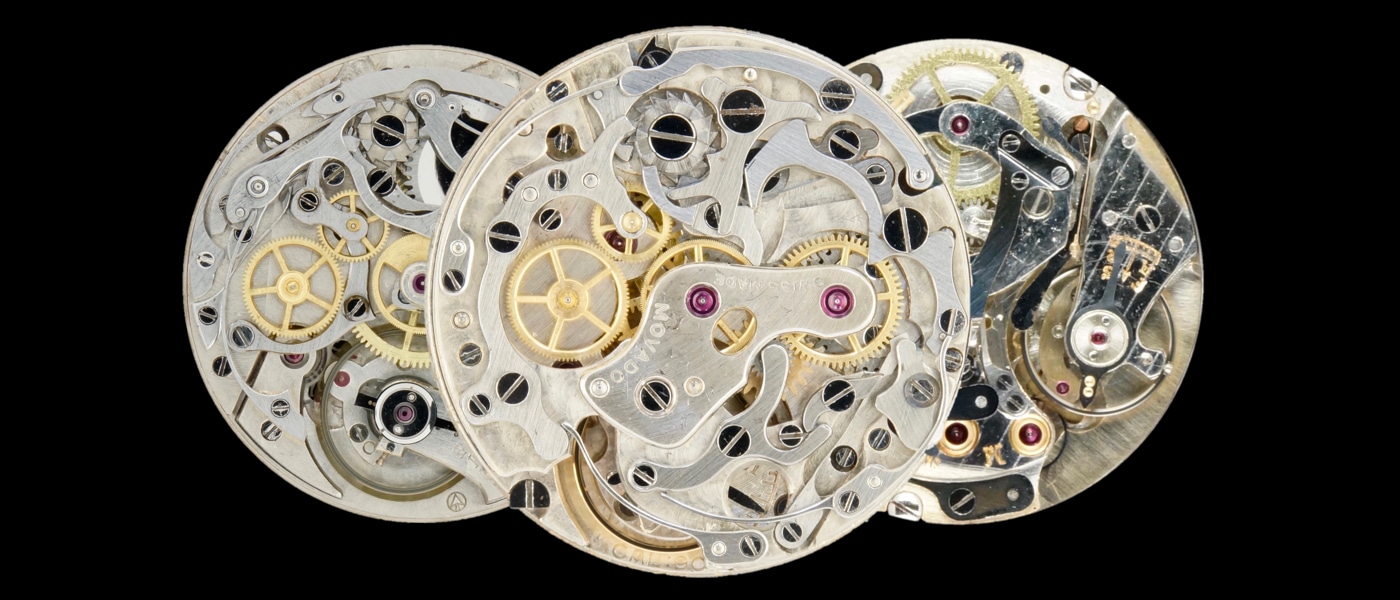

The calibre 4 series were nicely built and well-finished column wheel chronograph movements, easily recognisable by their sculpted bridge. A particularly intriguing feature of the calibre 42 was its unusual shape. Most chronograph calibres are round, but this one had an oval design, forcing the watch case to match its shape, a feature exclusive to Excelsior Park. The brand unfortunately disappeared in 1984, and it’s now the perfect example of a brand that deserves a renaissance. Today, you can find decent examples of Excelsior Park branded chronographs starting at 1,500 CHF, climbing to 10,000 CHF for a rarer reference.

2. Angelus

In 1891, three pious brothers founded Angelus in the watchmaking hotbed of Le Locle, in the canton of Neuchâtel. Their ambition for Angelus was to make it a high-end watchmaking specialist. Accordingly, Angelus issued several patents for pocket chronographs, repeaters and alarms. In 1925, their first wristwatch chronograph was launched. The monopusher chronograph borrowed the VZ calibre, a reliable and technologically advanced movement, from movement manufacturer Valjoux. In parallel, the company developed its own in-house chronograph movement, the calibre 210. The company rapidly started partnering up with other watch manufacturers, including Zodiac, with whom they created the smallest 8-day watch movement, and Panerai, which borrowed several Angelus movements.

Let’s focus on a specific calibre, the Angelus SF 217, an in-house chronograph movement that was used and designed for the Chronodato models. Issued in the midst of WW2 (1942), the Chronodato was the first chronograph featuring a full calendar, in other words displaying the day, the date and the month. The watch became a bestseller in Switzerland and Angelus capitalised quickly on this success by advertising it as the centrepiece of their collection. With a lifespan of more than 10 years, the Chronodato family was issued with various styles of dials, cases and case materials.

The layout of the dial was smart and elegant: the day was displayed in a small aperture just above the 6; the month was symmetrically located just under the 12, and finally the date was subtly revealed around the periphery of the dial in a clockwise manner by a red arrow hand. The 17-jewel column wheel calibre was one of the most complicated chronographs out there, bringing the brand credibility and fame, and forcing Valjoux to react quickly to come up with the Valjoux 72C calibre a few years after the SF217. The brand then updated the SF217 with the equally beautiful Chrono-Datoluxe, adding a moon phase complication and removing the day aperture. Nevertheless, the competition was now ready and well-equipped, and the model wasn’t successful as its predecessor.

Like Excelsior Park, Angelus wasn’t able to survive the massive hit of the quartz crisis, and disappeared in the 1970s. Relaunched recently with a different philosophy and a modern approach, the brand is now competing in the niche market of ultra-complicated watches. Being complex to maintain and unique in their layout and design, Chronodato chronographs are today hard to repair, as parts are becoming scarce. Their poor resistance to dust and humidity, due to the pushers used to operate the calendar, make it particularly difficult to find them in mint condition. However, you can still come across decent examples between 2,500 CHF and 4,000 CHF, a relatively interesting price if you take into consideration the history of the brand and the complexity of the calibre.

3. Minerva

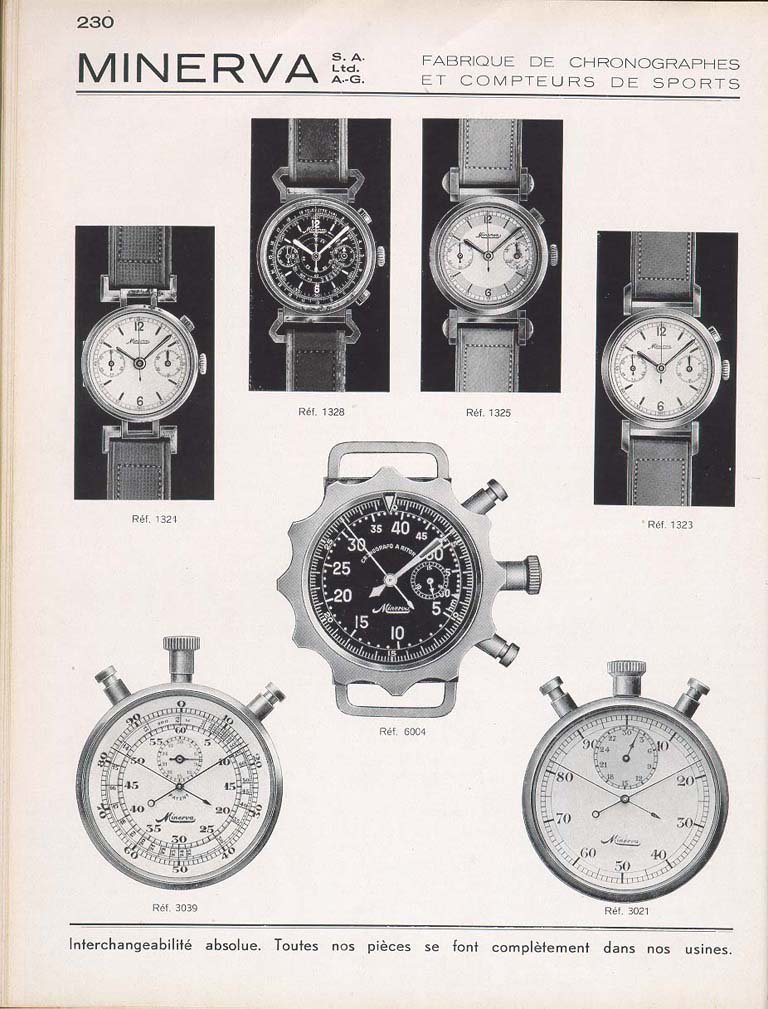

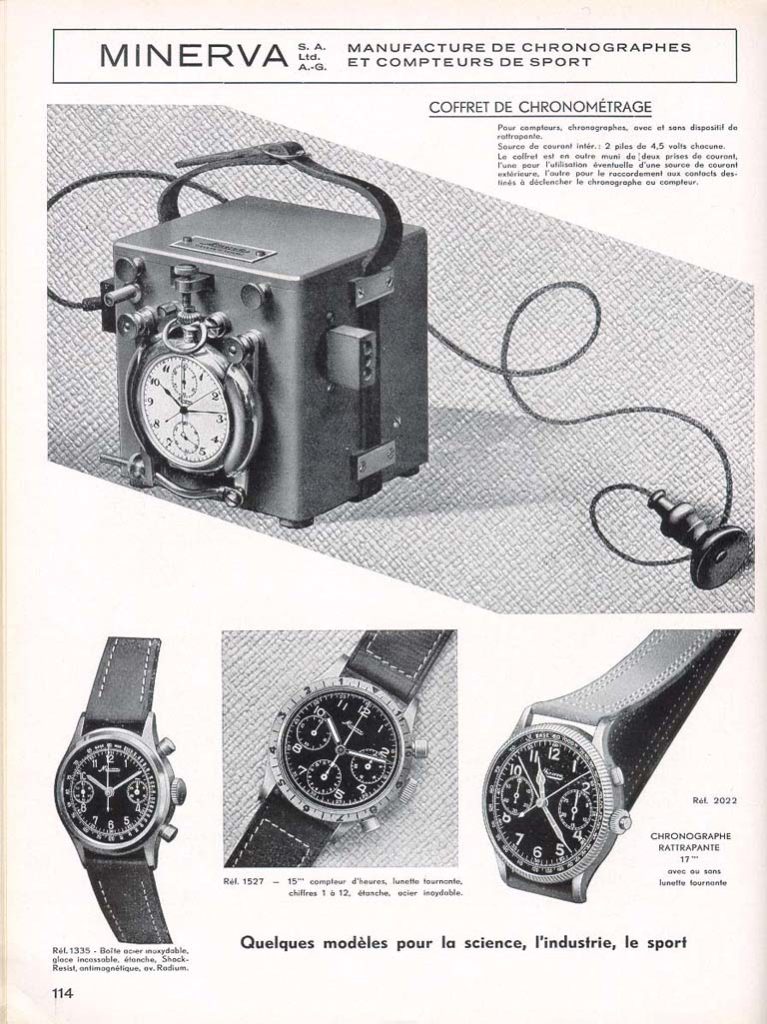

A small town called Villeret in the Bernese Jura, not far from the major horological centre of St-Imier, is where the brand Minerva was established. Founded in 1858 by two brothers, the company was initially named “H. & C. Robert”. In the 20th century, after changing the name of the company several times, the establishment slowly started to be recognised for its work, and particularly for its movements. Like Excelsior Park, the company began to forge links with the sports timekeeping world, consequently shifting its production towards sports stopwatches and chronographs. In fact, the Villeret-based manufacture was among the first companies to dive into the chronograph market.

In 1908, the calibre 9-CH, their first pocket chronograph, was invented – the precursor of what would become Minerva’s core identity and pride, the CH family. In parallel, the company also understood at an early stage that wristwatches would become the future of watchmaking and was among the first companies to make and sell their own variants. With the higher purchasing power of the 1930s, which resulted in a democratisation of watches, a large part of the watch industry shifted its focus towards sport watches and therefore chronographs, which afforded the company greater credibility and legitimacy. This strategy resulted in Minerva being awarded the title of official timing partner of the Olympic Games of Garmisch-Partenkirchen in 1936. At that time, the company was among the few brands that were producing their own chronograph calibres.

But let’s focus on one in particular, the 13-20 CH. It is recognised among collectors as one of the most beautiful in-house movements ever produced, right behind Longines’ top-of-the-line calibres. Initially designed as a column wheel mono-pusher chronograph, the calibre was subsequently improved into a double-pusher and was used in waterproof cases. From the outside, the rather simple two-register layout belies the undeniably beautiful internal organs hidden inside the timepiece. On a more technical note, the clutch module is divided into two pieces, a rarity that is somewhat reminiscent of the Longines 13ZN calibre.

Furthermore, there is no stopper/brake, which means that the hammer can only be rearmed during the resetting phase, rather than during the starting phase. Again, a rare intricacy that makes the 13-20CH an intriguing and uniquely designed piece. Still relatively underrated on the vintage market, these Minerva calibres are gaining visibility due to their modern and rather confusing affiliation with Montblanc’s high-end timepieces, and also to their appearance at recent auction sales. The 13-20CH is a beautifully designed movement that perfectly represents the dedication, attention to detail and creativity of watchmakers from the first half of the 20th century.

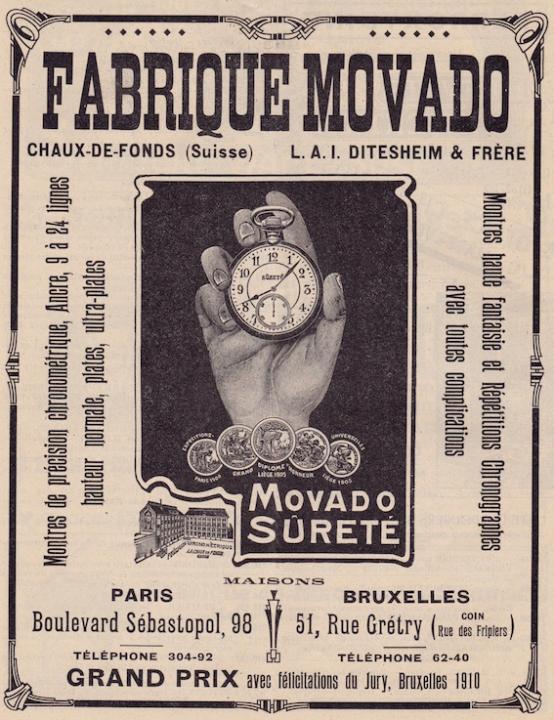

4. Movado

Everything started in 1881 with a 19-year-old watchmaker in La Chaux-de-Fonds who built his own watch movement from scratch, and developed a pocket watch workshop. The company took the name Movado 24 years later, a name signifying “continuous movement” in the international language Esperanto. The brand rapidly became famous for developing its own calibres as well as for their rather innovative and creative thinking in terms of concept and design. Movado manufactured ingenious watches such as the Plypan back in 1912, and the famous Ermeto, which were both stunning and original in their conception and layout.

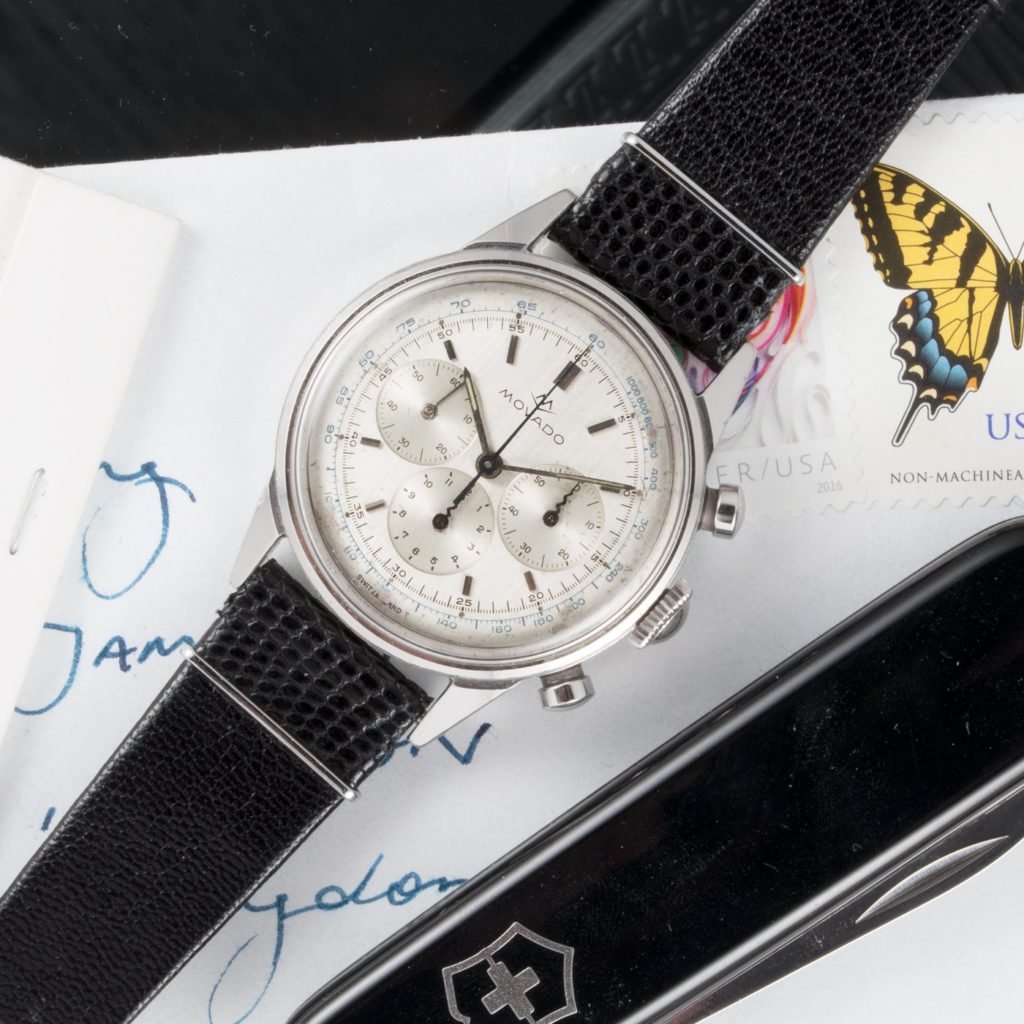

But let’s focus on the chronographs, and especially on the calibre 90M and its triple-register variant, the 95M. Developed in 1936 in collaboration with Louis-Elisée Piguet, the 90M calibre was launched two years later in 1938 (1939 for the 95M). The first intriguing thing you notice when you operate a Movado 90M is that the pushers function in the opposite way to the great majority of chronographs. In fact, the start/stop pusher is at 4 o’clock, while the one used to reset the chronograph is at 2, a small and quirky difference that makes the 90M calibres charming timepieces.

Technically, the movement compares with the best chronograph calibres of that era.

However, it is strikingly different in its design. First of all, where is the balance wheel? And what is that funny-looking bridge? In fact, the 90M and 95M are modular chronographs, meaning that the engine is actually on the dial side and hidden at first glance. The chronograph function is a module that sits on top of a more basic watch movement. Movado liked to say that these chronographs were actually the easiest to service due to their architecture.

Whether that is true or not, the unusual design gives this chronograph family a refreshing look that definitely makes these calibres a real find on the vintage market. Finally, there is the elegant yet intriguing design characterised by the snake-style minute hand. Proof, again, that Movado was committed to the idea of making things differently from the rest of the competition. For that alone, they deserve greater recognition.

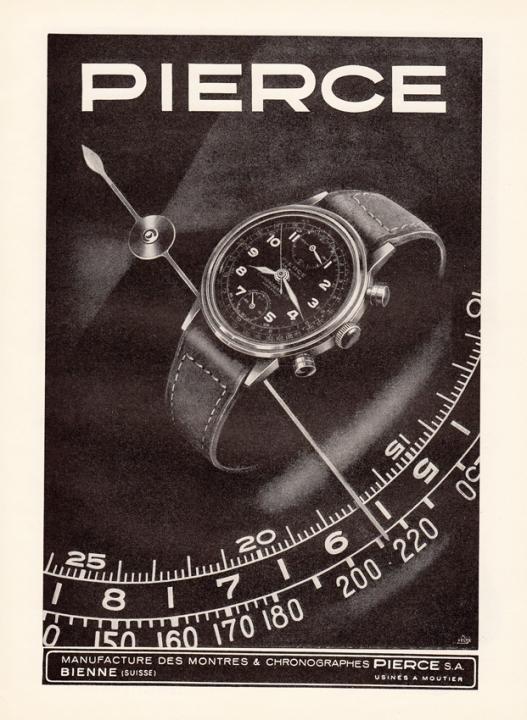

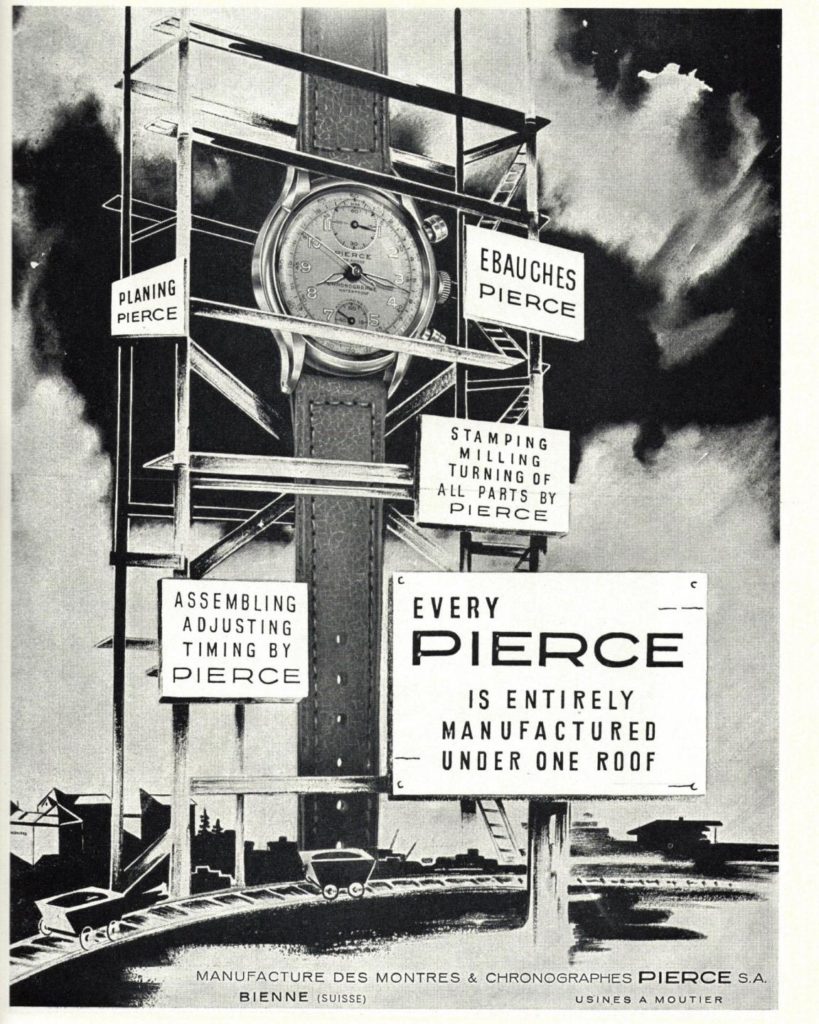

5. Pierce

In 1883 the Lévy brothers created “Léon Lévy Frères Manufactures des Montres et Chronographes Pierce SA” in the bilingual city of Biel/Bienne, Switzerland. Fast forward twenty-seven years and, in 1910, 1,500 of the town’s 24,000 inhabitants were employees of the company. Clearly, Pierce was already a big player in the industry. During the 1920s, Léon Lévy was approached by Ebauches S.A, who wanted Pierce to join the consortium. Léon, however, had a completely different direction in mind for his brand, and he refused the offer, allowing him to stay independent. This independence came at a cost: blacklisted by all the suppliers, Pierce couldn’t borrow or use pieces from the consortium companies, forcing the brand to come up with and develop their own manufacture calibres.

As a result, Pierce invented more than 30 different calibres throughout the company’s history, two of them being chronograph movement. By the mid-1930s, Léon felt the need to create an affordable chronograph for the masses, a particularly difficult at that time. Starting from scratch, he designed a movement (Calibre 130) built around a central wheel, enabling him to get rid of many springs and levers and consequently cut costs. Léon also invented a vertical friction clutch to engage the chronograph. Although frequently used in the watch industry today, it was a first at that time.

However, this strange yet ingenious architecture forced him to place the two registers in a 12 and 6 o’clock position, creating a rather unusual dial layout. The first watch sold with this calibre was launched in 1936 and became an instant success. In 1939 a two-pusher version came out and, a few years later, it became the official watch of Trans Caribbean Airlines pilots. After that, the British Royal Airforce placed an order for fighter pilots and other aviation personnel. At a certain point, the company decided to use plastic for the central wheel. Although hyped as a revolutionary material back in the day, it was mostly a way for the company to get cheaper parts.

That decision is today considered a mistake, as the plastic weakened the entire movement and sometimes led to the destruction of the wheel itself. For watchmakers, it was a nightmare to repair; for collectors, it became the perfect watch to bully. Sure, the calibre 130 wasn’t built with the standards and materials reserved for high-end chronographs, but it nonetheless helped to introduce this renowned complication to a wider customer base. Technically interesting and innovative in many ways, these Pierce chronographs can be found at really attractive prices. Just bear in mind that your local watchmaker may not necessarily agree to work on them.