Louis Moinet presents an artifact that may change how we look at the history of timekeeping.

The Swiss firm Les Ateliers Louis Moinet SA has unveiled a timekeeping device from the early 19th century that may be the first chronograph ever created. Known as a compteur de tierces – the term “chronograph” had not yet been invented – the device was built by French watchmaker Louis Moinet between 1815 and 1816.

It is not a watch: it does not tell time, but measures intervals of time. The counter’s balance beats at 216,000 vibrations per hour (30 Hz), allowing its center-mounted hand to accurately measure intervals to 1/60 of a second over a 24-hour period, an astonishing feat for its time. (The term tierce, literally “third,” was used at the time to refer to 1/60 of a second.)

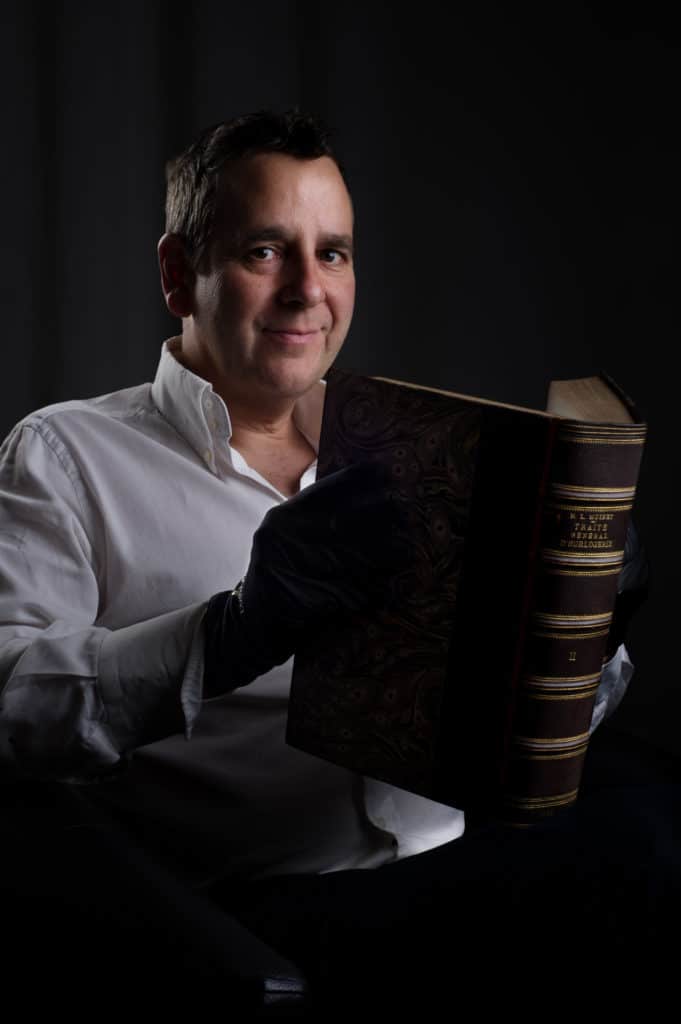

In a press conference held in Geneva on March 21, Jean-Marie Schaller, CEO of Les Ateliers Louis Moinet, who resurrected the Louis Moinet name 15 years ago, appeared with a number of watch experts to introduce the world to the Louis Moinet chronograph.

Les Ateliers LM purchased the counter at an auction at Christie’s in May of 2012 for $67,443. The instrument appears to have been very well maintained, and was sold by a family “of northern European royalty,” according to representatives of the brand. Hallmarks on the dust cover establish that construction of the instrument started in 1815 and was completed the following year.

Although the modern chronograph is thought of as a single complication, it was actually a series of distinct inventions, developed over a long time. The initial concept of a “chronograph” is attributed to Nicolas Mathieu Rieussec, who in 1821 created a device that used ink to measure time intervals.

Horse races were the prime purpose for which early chronographs were designed, and therefore they could clock intervals up to 10 minutes maximum. Rieussec’s first chronograph was rather large, but the idea was soon fitted to a pocketwatch size.

Adolphe Nicole developed a return-to-zero mechanism in 1844, which was first employed in a movement in 1862/ The rapid-reset is critical to the modern definition of “chronograph”; therefore Louis Moinet’s claim that the return-to-zero mechanism was fashioned nearly 30 years before Nicole is a remarkable one.

The accuracy of chronographs changed over time. Although the Rieussec chronograph could measure 1/5 of a second, more accurate time recording was thought to have taken much longer to develop. Edouard Heuer’s original Mikrograph stopwatch, in 1916, was the first timekeeper to measure 1/100 of a second, with a balance that oscillated at 360,000 vph. The notion that Louis Moinet’s counter measured 1/60 of a second 100 years before Heuer’s invention would be an astounding revelation.

The Louis Moinet chronograph has a silver case with a diameter of 57.7 mm. The signed dial features three subdials. A 24-hour counter is at 6 o’clock with a Breguet hand and Roman numerals to mark the first 12 hours. A 60-minute counter is at 11 o’clock, and a counter at 1 o’clock measures the seconds.

The counterpoised hand on the central axis tracks the 60ths of a second, with markers around the outside of the dial. All of the hands are in blued steel. The pusher at 12 o’clock starts and stops the mechanism, and another at 11 o’clock resets the 1/60-second hand to zero. All of the hands except the central one must be reset by hand.

The counter’s 30-Hz movement is made of brass. It has a ruby and steel cylinder escapement and a foliot balance with platinum weights for adjustment. The state of wind for the counter can be viewed through an aperture in the dust cover. The Louis Moinet firm claims the watch has a power reserve of “more than 30 hours,” and the oiled rubies of the escapement apparently reduce energy consumption to make this possible.

Moinet intended his compteur de tierces to be used for astronomical measurement. In order to accurately record the successive passages of a star through the sky, it needed to have a power reserve of over 24 hours. And by measuring down to the 60th of a second, Moinet could accurately set the distance between reticle lines on his telescope.

Moinet is one of the lesser-known figures in horological history when compared to contemporary watchmakers like Breguet and Lépine. Born in Bourges in 1768, Moinet studied sculpture, painting, and architecture, and lived for a time in Italy.

He became a professor at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris and devoted himself more and more to watchmaking, eventually being named president of the Société Chronométrique de Paris. He made clocks for major figures of the time, including Napoleon, Thomas Jefferson, and King George IV. His 1848 text, the “Traité d’Horlogerie,” was a seminal work on watchmaking techniques, and also includes a description of the compteur.

The news of the Louis Moinet chronograph shocked many in the watch world. The sudden revelation of this watch after 197 years may seriously recast the watch history of the 19th century. Dominique Fléchon, watch historian and Cultural Council member for the Fondation de la Haute Horlogerie, said he was “astounded” by the counter.

“On the technical level, you have to realize that this is the first time, to my knowledge, that we can measure 1/60 seconds entirely by mechanical means,” he said. In a letter to Les Ateliers Louis Moinet, Jean-Michel Piguet and Ludwig Oechslin of the Musée International d’Horlogerie said that the counter was “of remarkable workmanship and innovative for its era.”