Even in the traditional Swiss watchmaking industry, it’s something truly special when, like Vacheron Constantin, a manufacture can look back on more than a quarter of a millennium. Using new sources, we trace Vacheron Constantin’s unique business history.

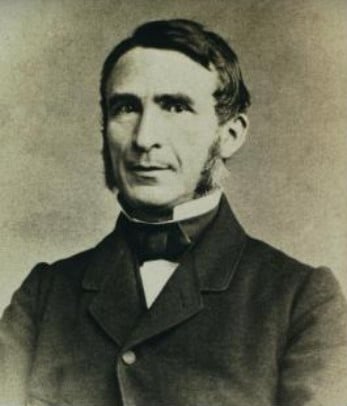

When Jean-Marc Vacheron founded his business in 1755, the world had not yet begun to feel the icy, metallic touch of the Industrial Revolution, whose dawn lay a few years ahead. The craft of watchmaking still proceeded at its accustomed, leisurely pace.

Approximately 800 horological craftsmen were active in Geneva at this time. Geneva, together with the Neuchâtel – Le Locle region and the Vallée de Joux, were the cradles of the watchmaker’s art. The watchmakers were called cabinotiers in honor of the well-lit “cabinets” on the top floors of the houses in Geneva’s Saint-Gervais neighborhood where they worked. Their tasks were assigned to them by établisseurs, manufacturers who bought and assembled all the parts needed to produce complete watches. Under the steady scrutiny of a master watchmaker, as many as eight cabinotiers labored in each atelier.

According to accounts of the time, a typical cabinotier was an artist, a learned man and a bohemian all rolled into one. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who wrote that he had acquired his love of reading in his father’s horological “cabinet,” reported firsthand about these “aristocrats of the working class.” Rousseau observed that “a watchmaker from Paris cannot talk about anything except watches, but a watchmaker from Geneva can speak with great eloquence about every topic and among every circle of society into which he is introduced.” Cabinotiers enjoyed a variety of privileges compared to ordinary industrial workers: they earned about twice as much and only had to work until 3 p.m.

Jean-Marc Vacheron was born the son of a weaver in 1731. By the age of 20, he was already a multitalented watchmaker and had developed many diverse interests. After completing his apprenticeship, he found his way into the elite circle of Geneva’s cabinotiers. But he wasn’t entirely satisfied with the contemplative existence of a cabinotier, so he opened a watch atelier of his own in 1755 in the old city of Geneva, the so-called “Cité,” where he employed one or perhaps even two apprentices. His timepieces naturally bore the name “Jean-Marc Vacheron.”

There is, however, another version of the story of how Vacheron & Constantin began. This tale is found in the annals of Charles Constantin, penned in 1940. Much of the information in this article comes from this manuscript. Constantin’s prose contains no information about the personal life of the firm’s founder, nor does it offer any facts about his early business activities. His version puts the date of the enterprise’s beginning in the year 1785, when Abraham Vacheron first appeared with his own signature. Nearly 200 years would pass before it became possible to determine exactly when the Vacheron Constantin firm was first founded.

In 1952, Eugène Jacquet, the curator of the watch collection of the city of Geneva, discovered Jean-Marc Vacheron’s articles of apprenticeship from 1755, the year which has been acknowledged ever since as the date of the firm’s founding. Between 1868 and 1870, Charles Vacheron had asked the archive of the city of Geneva to investigate the date of his firm’s founding. The results of those investigations likewise mentioned the year 1755, but the date could not be confirmed before Charles Vacheron’s death in 1870.

The times have not always been easy for Vacheron Constantin. A notarially certified document records that a loan of 1000 pounds silver was granted to Jean-Marc Vacheron on September 29, 1773. This sum could be related to the death of his aged father, Jean-Jacques Vacheron, on February 11 of the same year, or the loan may have been necessary because of the inclement economic climate that prevailed at the time, when hunger was a fact of daily life and few buyers could be found for the luxurious merchandise of the Genevan industry.

This difficult epoch exacted its financial tribute, and not only from Jean-Marc Vacheron. A well-informed author, writing in the “Avis du Compère Perret” newspaper, analyzed the disagreeable situation with a sarcastic undertone: “In my opinion, we [Genevans] ought to learn to be a bit duller and dumber. I ask: Why does the Fabrique de Neuchâtel run so smoothly, while we thirstily extend our tongues till they’re as long as our forearms? Those mountain people simply don’t party; they drink no coffee after their meals; they don’t engage in bill brokerage; and they don’t go the theater in Châtelaine, as do our Rousseau disciples against the rules of their master. They work twelve hours a day, they keep their wives and children company, and they’re happy to do so.”

We do know that Jean-Marc Vacheron experienced difficult times. In 1782, after the failed revolution in Geneva, the city was occupied by a combined force dispatched by the French and Sardinian monarchs, along with soldiers from the Canton of Bern. The occupiers exhausted the city to the point of near starvation and, to make matters worse, they also subjugated it from a commercial point of view. Soon afterwards, beginning in 1789, Geneva and its fabrique, as its watch industry was known, began feeling the consequences of the French revolution.

Jean-Marc, the proud father of five living children, struggled against various obstacles. As was usual in watchmaking families, his sons Louis André (born in 1755) and Abraham (born in 1760) had begun following in his footsteps. In all likelihood, he had personally trained them in the family’s traditional métier. The older brother signed his products “Louis André Vacheron”; the younger sibling initially signed them “Abraham Vacheron” starting in 1785 and then, after his marriage to Annette Girod in 1786, he began engraving them with the name “A. Vacheron Girod.”

The corporate name underwent further alterations in ensuing years. These changes were initially caused by the Ancien Régime and later by Swiss commercial legislation, both of which did not permit firms to use permanent names. Only after the establishment of joint-stock companies toward the end of the 19th century did it become possible to register a permanent name.

Prior to that time, a firm was obliged to do business under the name(s) of its owner(s). The name of the owner’s spouse was sometimes added to avoid mistaken identity. Individuals, rather than enterprises, occupied the foreground. For this reason, the watchmaking lineage of Louis André Vacheron, who died in 1814, ended around 1837 with the vanishing of the last traces left by his son Pierre André, who had sired no horologically active offspring. It thus remained for Jean-Marc, his son Abraham, and starting in 1810, Abraham’s son Jacques-Barthélemy to earn for the name “Vacheron” an immortal place in the history of watchmaking.

The political situation in Europe made life only seemingly easy for Jacques-Barthélemy. Napoleon Bonaparte had held sway in France since 1799 and the bourgeoisie further increased its prosperity, the insignia of which included, along with a little bell to ring for one’s servant, a luxurious timepiece in one’s pocket or atop one’s mantelpiece. The Fabrique de Genève gradually revived. Disintegrated markets and blocked distribution pathways, rebellions, hunger and misery had let to massive disturbances and rampant joblessness, but had not triggered a total collapse. Strong orientation toward Paris brought positive and negative consequences: the watchmaking industry in Geneva initially benefited from Napoleon’s Constinental System and its embargo against England, which excluded the watchmakers’ British colleagues from exporting wares to continental Europe; but as Napoleon’s star began to sink after the Russian campaign of 1812, the Fabrique de Genève likewise felt the effects of its decline.

One after another, continental European markets closed their gates and refused to accept deliveries from Geneva. Jacques-Barthélemy Vacheron was forced to concentrate his efforts on new territories. He did this without his father, whose retirement had probably been motivated by poor health, but with the active assistance of his uncle Barthélemy Girod in Paris, with whom he corresponded regularly. In one letter to his uncle, he wrote: “You ask me how things are going here in Geneva. Never before have the workers been in a worse situation. They couldn’t be unhappier. Most of the workshops are closed. Rumor has it that Darier and Galopin will soon close too.”

But there wasn’t only reason for lamentation: “We in Geneva have also received orders for your king from Rome; may it be God’s will that this will somewhat improve our lot.” The regent referred to here is Napoleon’s son, who was born on March 20, 1811 and whose second wife was Marie Louise, the daughter of Austrian Emperor Franz II. The trying times impelled watchmakers to broaden their portfolios and offer jewelry in addition to timepieces. In addition to these wares, Barthélemy Girod also temporarily sold to the French nobility other luxurious items such as spirits and choice fabrics. Only in this way was the subsidiary in Paris able to keep itself more or less out of red ink.

In 1813, the Geneva watch industry had recovered from the crisis, and the core business began to thrive again. Vacheron even did work for the legendary Abraham-Louis Breguet in Geneva.

Political events diminished the pleasure which should have been forthcoming from a long-awaited economic upswing. Agents sent by Napoleon knocked on the door to take erstwhile workers and turn them into soldiers. Vacheron alone was obliged to allow 80 of his active craftsmen to lay down their tools and pick up their muskets, a decline in his workforce which accordingly led to a drastic decrease in production.

In 1814, when the allies under the Prussian general Blücher marched into Paris and soon afterwards into Geneva, Jacques-Barthélemy Vacheron resignedly wrote: “Our facility has been totally inactive ever since the Germans arrived. We have tirelessly packed everything in order to be able to bring our wares out of harm’s way at a moment’s notice. The banks no longer have any money, and there’s reason to fear that anyone who has many debts to pay this month will be forced to file for bankruptcy.”

Jacques-Barthélemy was obliged to borrow money to assure the livelihood of his family and his business. Thanks to his excellent reputation in the city, it wasn’t particularly difficult for him to secure the necessary funds. On April 14, 1814, he again had reason to rejoice: “Peace, which we have so long yearned for, has put an end to our misfortune and now gives us reason to hope for a better future.

It seems certain that the Departement of Léman will become the twentieth Swiss canton, which would probably be the best solution for us too.” Jacques-Barthélemy’s prediction came true in 1815, when Geneva joined the Swiss Confederation. The Congress of Vienna enlarged the Geneva district to include the surrounding area, which was home to about 30 additional villages that had previously belonged to Savoy. The annexed territory also included Carouge. Future neutrality was assure.

After heated disagreements about future commercial plans, collaboration between Jacques-Barthélemy Vacheron and his uncle came to an end in 1816. The firm was renamed Vacheron-Chossat & Cie. on July 1. A new sign was affixed to the wall above the shop’s entrance in Geneva on August 5.

The new proprietor, Charles François, would henceforth concern himself with the business’s affairs on the shores of the Rhône, while Vacheron turned his attention to the increasingly important Italian market. Extensive journeys led him to the court of Turin, as well as to Milan, Bologna, Florence, Genoa and Livorno. He also kept an eye on Trieste, Naples and Sicily. Germany, he believed, was no longer suitable for trade, and France was too impoverished in the wake of the Napoleonic debacle. Courtly opulence and dreary customs stations alternated with one another. Mishaps occurred occasionally too, for example, the king of Piemonte was so fascinated by Vacheron’s most beautiful creation (a lavish timepiece with a built-in glockenspiel) that the regent enthusiastically disassembled the piece, severely damaging it in the process.

In addition to little treasures of this sort, Jacques-Barthélemy Vacheron sold various pocket-watches, some in ultra-slim version and others with repeater mechanisms. Their matching cases were available in smoothly unadorned, guilloche-embellished or diamond-studded versions. Though this assortment, which combined high quality and lavishness in equal measure, brought handsome profits. Vacheron wasn’t satisfied. “The seas are free,” he wrote, “but absolutely nothing is happening.” Once again, a period of economic doldrums prevailed in Europe between 1816 and 1818. The English were at fault this time because they were eager to sell, at virtually any even moderately acceptable price, the mountains of merchandise which had accumulated on the island during the continental embargo.

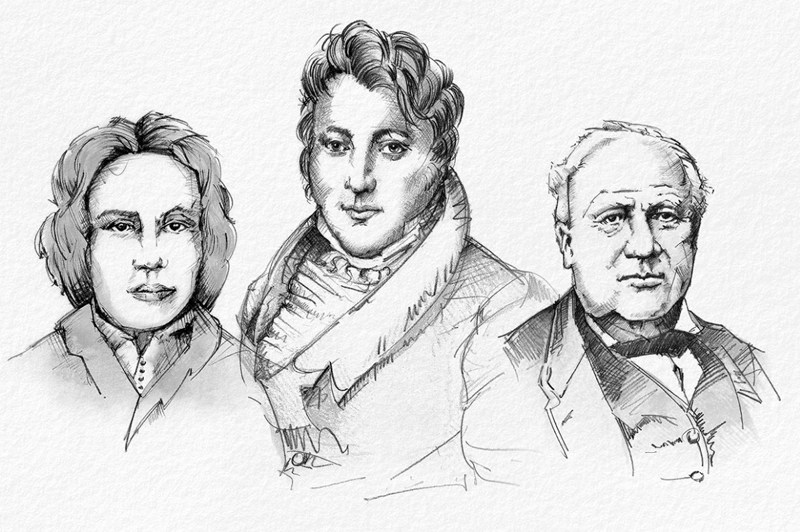

The realization gradually matured in Jacques-Barthélemy Vacheron’s mind that his ambitious business could not be remotely directed over the long term. During a trip he met François Constantin, the son of a prosperous textile and grain dealer. On April 1, 1819 he was invited to come aboard and the business’s name was accordingly changed to “Vacheron & Constantin.” Along with capital urgently needed to support further growth, the new partner also contributed his remarkable sense of business which he had acquired as a salesman for the respected F. Bautte watch business.

François Constantin straightaway climbed aboard a coach and departed for foreign destinations. Fisticuffs with highwaymen were a pesky fact of daily life. Looking askance at Constantin’s unconventional and extravagant style, respectable Genevan watchmakers began to whisper about the “decline of good morals” and to speculate that he would be more likely to drive his business into ruin than to shepherd it toward flourishing prosperity. François Constantin had a hot temper, and whenever someone attacked his company, he would challenge them to a duel.

Fortunately, his associates ultimately succeeded in discouraging him from pursuing the potentially lethal project. He was fond of quoting an adage, of which he himself was the author, which would accompany the manufacture throughout subsequent decades: Faire mieux si possible, ce qui est toujours possible! (Do better if possible, and that is always possible!)

Meanwhile, Jacques-Barthélemy Vacheron took care of the business’s internal affairs. He adapted the enterprise’s technical status and capabilities to satisfy the diverse and sometimes rather outré desires of its well-heeled clientele. Alongside the traditional top quality merchandise, growing markets also demanded and received a second line with different names. Though it is not known in what form the gradation occurred, it is certain that these wares were signed either “Abm. Vacheron à Genève” or “Chossat & Cie.” rather than “Vacheron & Constantin.”

To properly appreciate the achievements of the 31-year-old Constantin, one must imagine oneself transported through time and into his era. Along with economic crisis and the regency of Louis XVIII in France, this was also an epoch of prohibitive import tariffs which individual states sometimes unexpectedly revised overnight. Valuable timepieces were not infrequently damaged, destroyed or summarily confiscated during inspections.

Customs officials, eager to wreak revenge on the Genevans for having annexed part of Savoy in 1816, arbitrarily imposed monetary penalties. To make matters worse, the business had to contend with more than a few tardy payers, as well as certain noblemen who, when François Constantin arrived at their door to deliver a completed timepiece, were apt to suffer lapses of memory and suddenly become unable to recall ever having placed an order for a lavish watch.

The ingenious traveling salesman devised a clever expedient to protect himself against highwaymen. The costly timepieces were ensconced inside enormous chests which were so bulky that criminals couldn’t easily abscond with them. Iron fittings, complicated locks and secret compartments made it very difficult to break into these “vaults.”

But Constantin wasn’t only ingenious; he also had a savvy sense for political developments. His skilful efforts helped the business add ambassadors, counts, princes and dukes to its elite clientele. As the situation progressively deteriorated in the important Italian and Austrian markets starting in 1821, he focused his efforts on adding other countries to his export territories. This was a difficult project, as can be inferred by bearing in mind the abovementioned political conditions. Nonetheless, the Genevans sent their first watches across the Atlantic aboard vessels bound for North America in 1830, and ticking merchandise began coming ashore at South American ports a decade later.

The two proprietors and visionaries asked themselves a provocative question in 1839: How could their firm increase the quantity of its watches without adversely affecting their quality? In the course of his deliberations, Jacques-Barthélemy’s agile mind recalled an ingenious watchmaker and inventor named Georges-Auguste Leschot. After conducting lengthy and arduous experiments involving the depth of penetration and the lockingangle of lever escapements, in 1825 Leschot had quietly begun inventing various devices to enhance the precision of the serial manufacture of individual components for watch movements. In this way, Leschot and his partner Malignon were soon able to supply watchmaking companies with machine-made lever escapements at unbeatably low prices.

But these components alone were only part of the solution. The Fabrique de Genève demanded more. The brand was avidly interested in all of the components needed to more efficiently manufacture accurately running watches. This entailed an extensive machine park which was too large and too costly for Leschot to develop from his own resources alone. On the other hand, the industrialists were well aware that the significant gain in the precision with which the parts were manufactured would lead to a corresponding decrease in the amount of individual post-processing required when the movements were assembled. The resulting interchangeability of parts would also benefit after-sales and improve customer service. Such prospects triggered an optimistic rise in the pulse rates of the cost-plagued industrialists, but the selfsame visions dismayed the repasseurs, who feared that interchangeable parts would drastically reduce the amount of post-processing work.

Though they strove manfully against the innovation, the repasseurs were unable to stem the tides of progress, which swept into Vacheron & Constantin soon after June 29, 1839, when a contract was signed with Leschot. Among other clauses, the agreement specified an annual investment of 4,000 francs for new machinery to produce various movements with lever and cylinder escapements. The contract promised Leschot that as soon as these innovative machines were running smoothly, “you shall share in our profits. Instead of a fixed sum of 4,000 francs, from that time on you shall receive one-fifth of our net profits.” The future of this project was uncertain because no one could know in advance whether the new production methods would indeed result in what Vacheron, Constantin and Leschot hoped: namely, precision watches that would be only marginally more costly than comparable products of lesser quality.

Leschot indefatigably labored to implement his ideas. Two years later, a variety of machines had been installed in the workshops, where they evoked universal astonishment. Among these devices was a kind of milling machine that functioned according to the same fundamental principles as a pantograph. With its help, a large template could be scanned at one end, while the other end simultaneously manufactured smaller pieces with exactly the same shape and proportions.

Not only did this production method work comparatively quickly and simply, it also drastically improved the precision and significantly increased the number of units that could be produced. An innovative drilling and turning machine was capable of positioning holes and oil sinks at precisely the same location every time. Other turning and milling machines processed plates, bridges and cocks, or cut the teeth for escape-wheels and the notches for pallet-stones in delicate watch-pallets.

With more than a little help from such machinery, the mechanized production of new and highly precise calibers commenced at Vacheron & Constantin in 1841. The voices of watchmakers who had loudly bemoaned these innovations soon became progressively quieter. Their anxieties about the anticipated loss of their jobs proved unfounded. But instead of repeating the same old traditional tasks, they were now entrusted with new responsibilities, e.g. intensifying manual finishing to mechanically produced components in order to raise the quality of these parts to the highest possible standard.

Georges-Auguste Leschot repaid the trust placed in him by serving long and faithfully. Thanks to Leschot, who continued to improve and optimize his machines until 1882, Vacheron & Constantin deserves to be regarded as an unchallenged pioneer in the precise mechanical manufacture of watch movements. But that’s not all: the business has been a genuine manufacture since 1841, and it also possesses highly accurate records about each and every timepiece produced on its premises. The school of watchmaking in Geneva honored Leschot in 1888, when it named one of its classes after the trailblazing mechanician.

In 1825, at the tender age of 13, Jacques-Barthélemy Vacheron’s son Charles César had begun his course of studies at the newly established “Ecole de blanc” in Geneva. The youth’s father wrote to Constantin: “César’s classes will begin on the 20th. The students work from 5 a.m. To 6 p.m. Each day’s lessons include one hour of applied mathematics. I insisted to the school committee that César must be prepared to someday take over the directorship of the business.” This paternal intervention prompted the committee to teach the boy English and art history, and to give him additional training in mathematics.

Before he was permitted to join the family business, César first had to work as a trainee under the tutelage of a Genevan watchmaker who was one of his father’s friends and who, in good old cabinotier tradition, was also respected as a talented poet and composer. César admiringly observed the precision and skillfulness with with this watchmaker manipulated tiny files and other “primitive” tools. Ultimately, the quality and the perfect shape of a complex piece always depend upon the dexterity and patience of the watchmaker who fits and assembles its parts. These skills are further augmented by ample experience and a mysterious “sixth sense” which enable a watchmaker to know when the wheels and the pivots of the arbors have exactly the right amount of “play.”

One year prior to the date when the penultimate Vacheron would join it, the business was relocated to the “Tour de l’Ile.” This move also served Jacques-Barthélemy Vacheron as a timely opportunity to retire from his erstwhile position as director. Afterwards, François Constantin collaborated with Charles César Vacheron. François Constantin ceased his eminently successful travels and retired from business dealings in 1849.

Vacheron & Constantin delivered one of its timepieces to the emperor of China in 1865. Jean-François Constantin, a nephew of François Constantin and a co-owner, unexpectedly left the firm two years later to become and employee of another company, for which he worked as a watch salesman. With his departure from the family business, the name was changed to “César Vacheron & Co.” When César’s son Charles Vacheron took charge of the business in 1869, he renamed it “Charles Vacheron & Cie.” His tenure was brief because he succumbed to a serious illness and died the following year at the age of 24. On his deathbed, he asked to see the last watch manufactured in the atelier. His request was honored, and one of his last acts was to admire the miniature timepiece, which had been ordered by Czar Alexander II of Russia.

A woman now took charge of the business, and a second lady stood beside her. This was a sensational event in the Swiss watchmaking industry. Misogynists in Geneva’s watchmaking guild prophesied that this “women’s economy” couldn’t possibly thrive. But they were proven wrong by Charles César Vacheron’s widow Laure Vacheron-Pernessin and Jacques-Barthélemy’s 88-year-old widow Cathérine-Etiennette Vacheron. Although the elder lady never officially belonged to the business’s directorship, she initiated a series of intelligent measures during the five years of her collaboration with the younger widow.

Many of these initiatives would come to be regarded as having laid the foundations for the further evolution of the manufacture into the 20th century. First, the firm’s name was changed to “ Vve. César Vacheron & Cie.” Another step was the decision to participate, from the very beginning in 1872, in the precision competitions at Geneva Observatory and thus to win important awards for the company. It was also clever to ponder how the familiar and respected name “Vacheron & Constantin” could be used again. The two ladies also began searching for an experienced manager. Their headhunt came to a successful conclusion in 1875, when they hired Philippe-Auguste Weiss as director.

After negotiations with Jean-François Constantin, he came back and was again authorized to serve as sole signatory for legally binding contracts and agreements. The business was transferred to Laure Vacheron-Pernessin and Jean-François Constantin and was forthwith registered as “Vacheron & Constantin.” The two widows were also responsible for relocating the workshops, offices and salesrooms in a move which took place immediately after the firm’s renaming. The new venue was at the Quai des Moulins on the Rhône Island in the heart if Geneva.

The manufacture’s subsequent years were likewise distinguished by trailblazing decisions, one of which occurred immediately after a new law to protect trademarks and logos was passed in 1880. The manufacture registered four different trademarks and names which would be used to designate its various movements and cases. All four shared one common denominator: namely, the phrase “Vacheron & Constantin, fabricants, Genève” augmented by the words “Horlogerie et boîtes de montres.” Two others have a distinctive feature which is still recognized around the world as the symbol of Vacheron & Constantin: the Maltese cross. The origins of this logo can be traced to the shape of a component which regulated the tension in the mainsprings of early watches.

Cathérine-Etiennette Vacheron celebrated her 100th birthday in 1882. She died the following year, just six weeks after her 101st birthday. Laure Vacheron-Pernessin, the former directress, passed away in 1887. The business was subsequently transformed into a joint-stock company with the name “Vacheron & Constantin, Ancienne Fabrique SA.” The words “Ancienne Fabrique” were eliminated in 1896.

The first wristwatches joined the brand’s collection in 1888. These newfangled items were eagerly purchased by customers who lived in metropolises where fashionable trends were set and followed. Demand rose quickly, and the number of watches produced increased accordingly. The business luxuriated in a golden age which enabled the share capital to be doubled to 600,000 Swiss francs in 1911. Charles Constantin joined the firm on June 1, 1914 and remained with it until his retirement, when he relinquished his posts as director and member of the administrative council.

The long period of flourishing came to an end in 1914. Confusion and uncertainty spawned by the First World War reduced demand for the company’s merchandise, and numerous orders, which had already been received, were subsequently cancelled for various reasons. These orders couldn’t have been filled very quickly anyhow because general mobilization of able-bodied men had reduced the workforce and compelled many watchmakers to doff their aprons and don military uniforms. Charles Constantin was among the troops assigned to defend Switzerland’s northern frontier. The economic situation improved only marginally after war’s end, partly because the war-torn nations imposed restrictive import regulations to prevent the export of capital which was desperately needed to repair domestic damage caused by the recently concluded hostilities.

Orders from the czarist court in Russia arrived in 1916, but these were little more than a straw fire, which was soon snuffed by the October Revolution of 1917. The same was true of orders placed by the USA, which had entered the war in 1917 and had established a procurement office in Bern to supply the American Expeditionary Forces. When the Americans asked the Genevan manufacture to provide timepieces for military purposes, Vacheron & Constantin agreed and soon became a major supplier. The firm participated in the watch exhibition in Geneva in 1920, but no significant upswing was forthcoming until 1922.

Then came “Black Friday” on October 24, 1929, when the stock markets crashed on Wall Street and triggered a global economic crisis. Many nations responded with protectionist measures. Their effects were so dire that Vacheron & Constantin plunged to a commercial nadir. Production and sales declined precipitously. The staff-one technician and 65 workers – assembled 1,810 ébauches in 1930. Karl Scheufele, the new agent for Germany, put a large quantity of watches into storage. No end to the economic malaise was in sight.

The business’s directors were compelled to take drastic measures in 1931, when salaries were slashed and working hours were shortened to 18 hours per week. The world’s markets were flooded with surplus merchandise. Luxury watches were the last thing consumers needed now. The management, which consisted of Emile Seidel, G.M. Grandjean, Henri Wallner and Charles Constantin, reduced production to a bare minimum. They also lowered prices and began using stell or silver cases in an attempt to attract new customers, e.g. Geneva’s streetcar company, which ordered 125 silver pocket-watches for its employees.

This order alone was by no means enough, so standard movements and cheaper products were created on the basis of stockpiled wares that had been written off long before. But the crisis had other consequences as well: new models, case shapes and complications were developed with tremendous creativity.

The few remaining ateliers produced only 211 movements in 1932. The next year began equally poorly, so workers were temporarily sent home. To provide at least a modicum of employment, some workers made silver heels for shoes in the style of Louis XV. As if the situation weren’t bad enough, rectangular wristwatches came into fashion in the 1930s. Their sudden popularity made the old stockpile of circular watches nearly worthless.

Reduced production continued in 1934. The staff was paid on a per-piece basis. To save money, Vacheron & Constantin (as well as Patek Philippe) terminated their participation in the annual chronometer competitions. When, according to the reckoning system used at the time, firm’s 150th anniversary arrived, a series 300 jubilee wristwatches with 11-ligne manual-winding Lépine movements were constructed. Because these calibers had mostly been written off, the wholesale price of the watches could be set at an astonishingly low 100 Swiss francs for timepieces with steel cases and 200 francs for watches with 18K gold cases. The anniversary collection was further augmented by rectangular wristwatches in steel and gold cases.

Vacheron & Constantin lacked the financial wherewithal to develop its own shaped calibers, so the decision-makers opted for “La Générale,” well known from the “Helvetia” brand, which supplied a meticulously crafted, 8-ligne, tonneau-shaped, hand-wound movement. Another initiative was the birth of the “Astral” sub-brand. Charles Constantin was so disheartened by his firm’s straits that he couldn’t bring himself to take into the business his children, who had since completed their academic studies. In their sted, his nephew Léon Constantin joined the firm to continue the family tradition.

The massive devaluation of the franc on September 26, 1936 helped revive the business. It also enabled the firm to increase the number of working hours for its staff to 43 hours per week. Despite these extra hours, 66 workers under the direction of two technicians were unable to fill all the orders. Although the manufacture was able to produce 3,000 watches per year, 1937 ended with 439 watches and movements that had been ordered but not yet delivered. This same year, Vacheron & Constantin debuted no fewer than five new calibers for wristwatches, and Egypt’s King Farouk added a bit of oriental glamour when he visited the shop on the Ile.”

The next year, 1938, was a decisive one for Vacheron & Constantin. When a co-worker suggested that the firm should also represent Jaeger-LeCoultre in Italy, negotiations began with the movement manufacture in the Vallée de Joux. During the course of these talks, Vacheron & Constantin’s financial difficulties were openly disclosed. A decision was reached in September 1938: the brand, which had been founded in 1755, would preserve its autonomy but nonetheless became a member of the S.A.P.I.C.

Group (Société Anonyme de Produits industriels et commerciaux), a holding of which the other members were Jaeger-LeCoultre’s sales organization in Lausanne and the Jaeger-LeCoultre movement factory in Le Sentier. Jaeger-LeCoultre relocated its sales organization from Lausanne to the “Ile” in Geneva, where important repairs were also performed. LeCoultre afterwards made ébauches for Vacheron & Constantin in LeSentier. The assembly of these ébauches continued to be done on the shores of the Rhône. Paul Lebet was chosen as delegate to the administrative council for all of the companies; Georges Keterer was appointed commercial director. In 1948, Ketterer became president of the firm, and from 1965, he was its major shareholder.

On July 18, 1955 – the same year which marked the manufacture’s 200th anniversary – the four statesmen Eisenhower, Eden, Bulganin and Faure met at the Palais des Nations in Geneva. At the conclusion of the conference, twenty citizens of Geneva each gave a Vacheron & Constantin wristwatch to the conferees. The back of each timepiece was engraved with a message: “May this watch always indicate happy hours for you, your people and the peace of the world.” Two years previously, in 1953 the Swiss government had given a coronation gift to the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth II, a gorgeous, diamond-studded Vacheron & Constantin.

In 1955, ordinary mortals could buy and ultra-slim gent’s wristwatch encasing the hand-wound Caliber 1003, which was a mere 1.64 millimeters tall. This was a world record. Another milestone in the race to construct the world’s slimmest watch was achieved in 1967, when Vacheron & Constantin and its movement supplier LeCoultre developed the self-winding Caliber 1120: this movement measured a mere 2.45 mm in height and had a central rotor which ran along a circular, beryllium-bronze track that glided atop ruby rollers.

Artisans in the Genevan workshops collaborated with the painter Raymond Moretti to create a timepiece which, when it debuted in the late 1970s, was the world’s most costly wristwatch: the Kallista, which means in Greek the “most beautiful,” combined 140 grams of gold with 130 carats of precious stones. It sold for around five million dollars, thus earning itself an entry in the Guinness Book of Records. No fewer than 6,000 man-hours of labor had been invested in its creation. Despite its exorbitant price, it found a buyer. The identity of its purchaser is unknown even to Vacheron Constantin, but the individual is rumored to have been the Sultan of Brunei.

Notwithstanding this superlative sale, the Quartz Crisis that beset the entire Swiss watchmaking industry also forced Vacheron Constantin to search for a financially strong partner. The person the manufacture found was a friend of the Ketterer Family: Sheikh Yamani, Saudi Arabia’s former oil minister, who took over 85% of Vacheron Constantin in 1987. The only problem was posed by the real estate of the “Tour de l’Ile,” because according to the so-called “Lex Friedrich,” foreign persons who intend to purchase land must first be granted permission by the responsible cantonal authorities. Sheikh Yamani was therefore obliged to leave the traditional building to other investors and rent space for himself in the traditional headquarters. He re-invested the money in the development of the company.

A fortunate hour tolled in 1996 when the Vendôme Group (now Richemont International SA) of the South African Rupert family decided to round out its portfolio of brands by acquiring the house of Vacheron Constantin. “That was a genuine stroke of good luck for us,” the firm’s former chief Claude-Daniel Proellochs declared at the time. “Vacheron Constantin could finally raise its flag on international markets in a style appropriate for a traditional enterprise of its eminent status.”

Today the firm’s brand-new, highly functional and contemporary-looking building in Plan-les-Ouates on the outskirts of Geneva embodies the lofty status of the brand in the luxury watch industry. When Sheikh Yamani came aboard in 1987, the watch manufacture manufactured approximately 3,400 watches each year. In 1996, the annual production increased to about 14,000 timepieces.

Since 2000, Vacheron Constantin has emphasized the term manufacture and the independence it entails. The beginning of this route back toward full-fledged manufacture status was made in the Vallée de Joux. The first movement from the year 2000, the tonneau-shaped tourbillon Caliber 1790, was followed by a new hand-wound movement: Caliber 1400. Additional manufacture calibers, with which Vacheron Constantin hopes to keep itself in the focal point of connoisseurs’ attention, will be forthcoming from joint development between Geneva and the Vallée de Joux.

The 120 coworkers in Vallée de Joux are responsible for the research and the development of mechanical movements, as well as for the manufacturing and fine processing of components. Finished movements, however, are not their métier. For good reasons, this portion of the work remains the responsibility of their colleagues in Geneva. Only afterwards can be products with the Maltese cross also be stamped with the prestigious official state of Geneva Quality Hallmark.

The new factory building, which is appropriately situated at 10, chemin du Tourbillon in Plan-les-Ouates, Geneva, opened its doors on October 9, 2004, following two years of planning and 18 months of construction work. This ended a long phase of dispersal, during which Vacheron Constantin’s staff of approximately 170 persons worked at various buildings scattered throughout the metropolis beside the Rhône.

After a competition among architects, Bernard Tschumi’s agency was commissioned to design a building, on a 30,000-square-meter plot of land, which would embody dynamism and longevity. The building’s shape was inspired by the Maltese cross. The gleaming silver of the edifice’s metal exterior represents the first trait, and its massive concrete foundation embodies the second attribute. Constructed from concrete, metal, wood and glass, the complex provides some 7,000 square meters of floor space for Vacheron Constantin’s 170 employees, of whom nearly 80 are watchmakers.

The Malte Squelette tourbillon with tonneau-shaped case surely ranks among the manufacture’s most outstanding products. Skilful artisans skeletonize the hand-wound movement, which perfectly fills the case, to the limits of feasibility and then lovingly engrave the remaining bars. The filigreed tourbillon occupies almost the entire lower half of the shaped movement, where it rotates around its own axis once per minute. The Malte Grande Classique encases the manufacture’s own Caliber 1400 and is extremely simple compared to the Malte Squelette. The MGC’s small, slim movement has a diameter of approximately 20 mm and height of 2.6 mm.

The Historiques Toledo 1952, which was launched in 2003, is based on a model that debuted in 1952, when quadratic cases were in fashion. Consumers in the early 1950s wanted extravagant and unconventional watchmaking. Then as now, Vacheron Constantin has never been satisfied with the merely ordinary, so the quadratic wristwatch, which also indicated the phases of the moon, was given an ergonomically rounded case with distinctive strap lugs. This was the reason for its nickname “Cioccolatone”.

The fascination of the new Historiques Chronomètre Royal 1907 lies in the fact that its officially COSC-certified precision isn’t obvious at first glance. The appeal of its self-winding Caliber 2460 SCC with Geneva Hallmark derives from exceptionally painstaking fine processing and meticulous adjustment in five positions and at three temperatures (8,23 and 38 degrees Celsius).

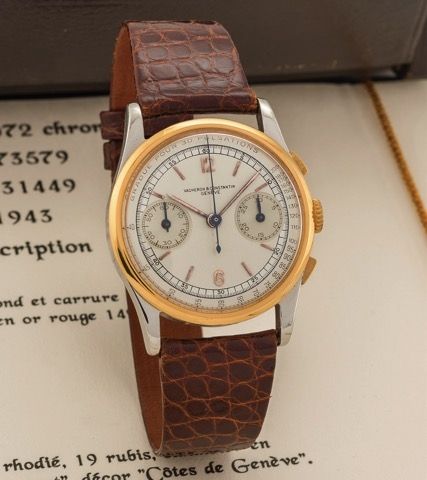

Vacheron Constantin debuted its first wristwatch chronograph exactly 90 years ago. The Malte chronograph continues this tradition. It encases the exclusive, carefully ennobled, hand-wound Caliber 1141, which only three watch brands use in their products. The special features of this caliber include a column-wheel, horizontal wheel coupling, and a balance that swings at a pace of 18,000 semi-oscillations per hour. Seldom encountered nowadays, this comparatively leisurely pace enables the chronograph to time intervals to the nearest fifth-of-a-second.

Vacheron Constantin devoted itself to the theme of the luxury sport wristwatch in the 1970s. The results of this dedication were the sporty 333 line that referred to the Overseas model of 1933, and the 222 line. The design of the latter was inspired by the look of a ship’s hatch. The “Triple Two” found its legitimate successor in the thoroughly distinctive Overseas, which debuted in 1996. Despite its eye-catching appearance, this line represents the top segment in the art of Swiss watchmaking. Vacheron Constantin helped the sporty Overseas celebrate its eighth birthday by giving it a cautious but impossible-to-overlook facelift.

Vacheron Constantin is the only watch manufacture in the world which can look back on 250 years of uninterrupted superlative achievements in the service of precious and very precisely measured time. The festivities surrounding the anniversary took place before an international audience which had gathered near the business’s traditional headquarters along the shore of the Rhône. But that wasn’t all.

At a much-noticed auction, the top prices paid for the 250 objects on the block demonstrated just how highly the brand’s global clientele of collectors and connoisseurs appreciate its ticking products. Vacheron Constantin also shone brilliantly with a small but exceedingly fine collection of outstanding horological achievements which were specially created and manufactured to commemorate the brand’s 250th birthday.

The most impressive of these was no doubt the Tour de l’Ile wristwatch, the msot complicated wristwatch ever produced in a series, which sonsists of 834 mechanical components and has a hand-wound movement with a tourbillon and a repeater strike-train. It offers sixteen different complications with the following indications: the phases of the moon, the night sky with the constellations, the equation of time with the times of sunrise and sunset, a perpetual calendar until 2100, the remaining power reserve, the amount of torque in the strike-train, and naturally also the hours and minutes. Inside the Jubilée 1755, which was manufactured in a limited edition of 1,755 pieces (1500 of each gold color, 250 in platinum, and five left to the manufacture’s own collection), the fine manufacture Caliber 2475 with rotor winding mechanism indicates the time, the day of the week and the date.

Vacheron Constantin again celebrated important birthdays in 2006. The first celebration commemorated the brand’s Overseas watch’s tenth anniversary with the launch of the trendy Dual Time in a 42-millimeter-diameter steel case. In addition to indicating the time in a second time zone, this model is also equipped with an inner case made of soft iron to protect the self-winding Caliber 1222 against the deleterious effects of magnetic fields. An equally remarkable anniversary occurred a few months later in 2006, exactly one-hundred years after the impressive salesrooms on the picturesque island in the Rhône had opened their doors for the first time on the ground floor in 1906. Following thorough renovations in accord with the style of the 21st century, these premises now shine with a new gleam. They are called the “Maison Vacheron Constantin en l’Ile.”