International (Watch Co.) Man of Mystery

IWC’s in-house historian reveals how the company’s American founder, Florentine Ariosto Jones, revolutionized watchmaking. IWC celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2018 with the release of the Jubilee collection at SIHH, a collection we covered in depth in our April issue. But how much do you know about Florentine Ariosto Jones, the New Englandborn watchmaker who established the International Watch Company in Schaffhausen in 1868 and ushered in a new era for the Swiss watchmaking industry in the process? We spoke with IWC historian David Seyffer prior to SIHH to get his insights into the man behind the brand. WT: What were some of the factors that led Florentine Ariosto Jones to leave the U.S. and come to Switzerland to make watches? DS:The most important reason was that his business plan was to produce watches for the U.S. market, and Switzerland had many more highly skilled workers for much lower wages at the time. In the U.S., there were a lot of watch companies competing hard to get the best and most skilled American watchmakers to work for them, and this drove wages in the U.S. higher. So, going to a country like Switzerland, which had really the best watchmakers in the world, and then have them produce watches to be sold in the U.S. market was a brilliant plan in those days.

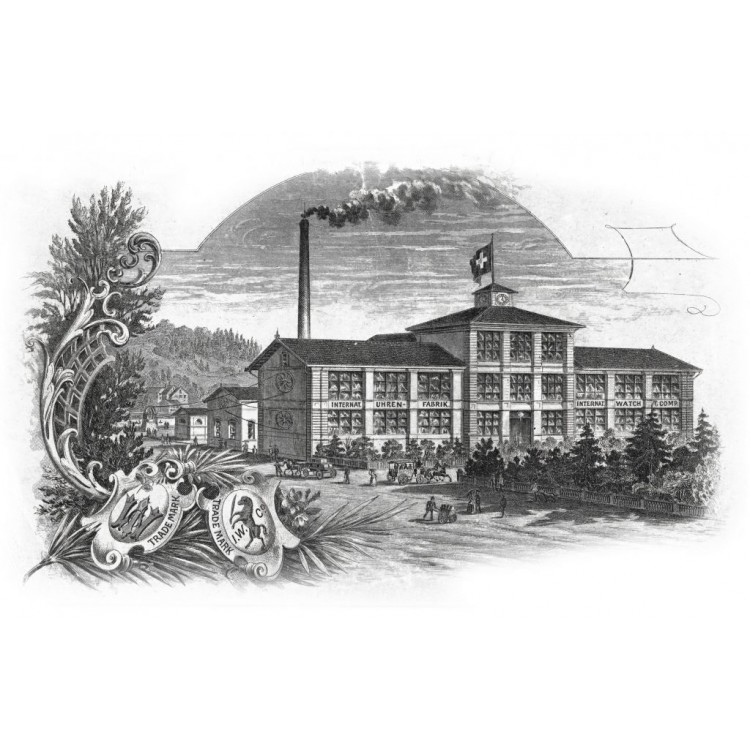

WT:Obviously, a lot of the Swiss watch industry, even at that time, was in places like the Vallée de Joux and around Geneva. So how did Jones come to choose Schaffhausen as the ideal spot for his company? DS:The answer is a little bit tricky, because we can only interpret from the sources that still exist. We know from his passport that Jones was traveling around Europe in 1867, during a very famous world exhibition in Paris, which others from the American watch industry also attended. Most probably, Jones took this chance to travel around Switzerland – and maybe Germany and France, all the locations where watches were produced in Europe – so he could see some options. Also, he was more interested in the eastern part of Switzerland because it was more convenient for trade with the U.S.A. and England. The western part of Switzerland was always more related to France because of the language and there were not so many business relationships between this area and the U.S. The government of Schaffhausen also offered him really low taxes because they wanted new start-up businesses to push the economy there. As a businessman, Jones simply realized it was the place to be. WT:Didn’t the geography also play a role in the location of the factory? DS: Exactly. The Rhine River was able to produce hydroelectric power – the government of Schaffhausen had implemented this – and this made the area a very attractive place for a young [industrial] business. Another consideration was the existing skilled workforce. Schaffhausen was the home of a large weapons manufacturer, which means there were lots of workers skilled at making really small and highly accurate metal parts. These were people who could be hired for watchmaking.

WT:What did Jones bring to Swiss watchmaking that had not previously been there? How did he change the industry as a whole? DS: His teachers were Aaron Lufkin Dennison and “the father of American watchmaking,” Edward Howard. Jones basically brought their very American system of watchmaking, with its industrialized production, to Switzerland and applied it to the process of making luxury watches, watches at a very high price level. This was different from American companies, like Waltham, which all wanted to mass-produce lower-priced watches. It was a complete restructuring of the [traditional] Swiss watchmaking process – you work under one roof, produce standardized parts; the whole production is highly integrated, with all the processes checked by supervisors. Under the old “cottage” system, parts would be produced in several places, assembled in one place and then sold. By the 1870s this was not competitive any more with the American system. Jones really was 10 years ahead of the general trend on that; it was quite a while before the western part of Switzerland caught on.

WT: What happened to Jones in the later years and what were the circumstances of him separating from the company that he founded? DS: It’s a bit of a sad story, in my opinion. Jones was always looking for investors, because as he built up production at IWC he needed a lot of money. It was like “Shark Tank” in 1874. IWC was founded as a shareholder company, and when you have shareholders, you have to please them. Some of the shareholders started challenging Jones, saying he promised them larger shares and more sales growth. And Jones was not, let’s say, very politically correct in his responses. The situation exploded in the autumn of 1875: some of the shareholders didn’t trust Jones anymore and wanted him out. On the other hand, the watchmakers and other employees all supported Jones. At the end of the day, Jones had to leave and make room for a new CEO. He returned to the U.S. from Schaffhausen and never returned to watchmaking again. What happened after he came back is mostly unknown; we know he worked for some other companies. WT: And he never did any other entrepreneurial things? DS:No, never. Perhaps this shows the passion he had for IWC: it was his company, and his employees still trusted him 100 percent. The Schaffhausen newspapers from this period were full of articles with comments from IWC employees and how they didn’t like how Jones was treated. We know that he suffered a disease that left him unable to walk at the end of his life, and he passed away in the United States. We are in fact very well informed about the later stages of Jones’s life, because he fought for the U.S. Army in the Civil War, and every soldier received a pension from the U.S. government. In the national archives in Washington, DC, there are letters from Jones to the U.S. Military and letters from his widow after he passed away. He was with the 13th regiment at Gettysburg, though not necessarily on the front lines.

WT: Would you say that Jones was sort of the Henry Ford of watchmaking? DS: I would give that distinction more to his teachers, Dennison and Howard, who largely invented watchmaking in America. If you look at any 19th-century American book about watchmaking, these two are regarded as heroes, the father figures of the whole process. Jones was the one who brought the process to Switzerland.