The beginning of the legendary watch Heuer Autavia

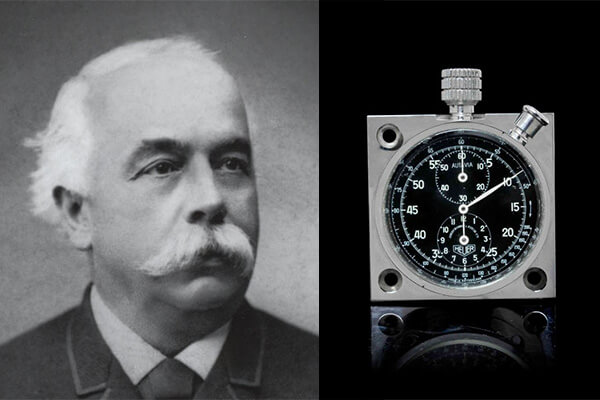

During the 1880s, chronograph became

increasingly popular with the rise of organised sporting events. In America,

they were sought after by racehorse owners, trainers and habitues of racecourses.

By 1882s,

Heuer had made sufficient improvements to the manufacture of chronograph

movements to be granted a patent for a perfected chronograph mechanism. The

result was a sports timer of superlative accuracy, but Heuer's ambition was to

produce significant numbers of chronographs and by bringing the cost down, put

them within reach of a larger number of people, an ambition he achieved with

the invention of the oscillating pinion, a component that remained at the heart

of chronograph, manufacture thereafter featuring in such legendary wristwatch

movements as the Valjoux 7750 and in today in-house calibre Heuer 01.

Edouard Heuer was phenomenally successful, and although he died at a tragically young age, he had amassed a fortune of over half a million Swiss francs. He also established a thriving business run by three successive generations of his family who have continued his legacy of innovation in the field of chronography, acquiring, for instance, the rights to manufacture waterproof chronograph cases.

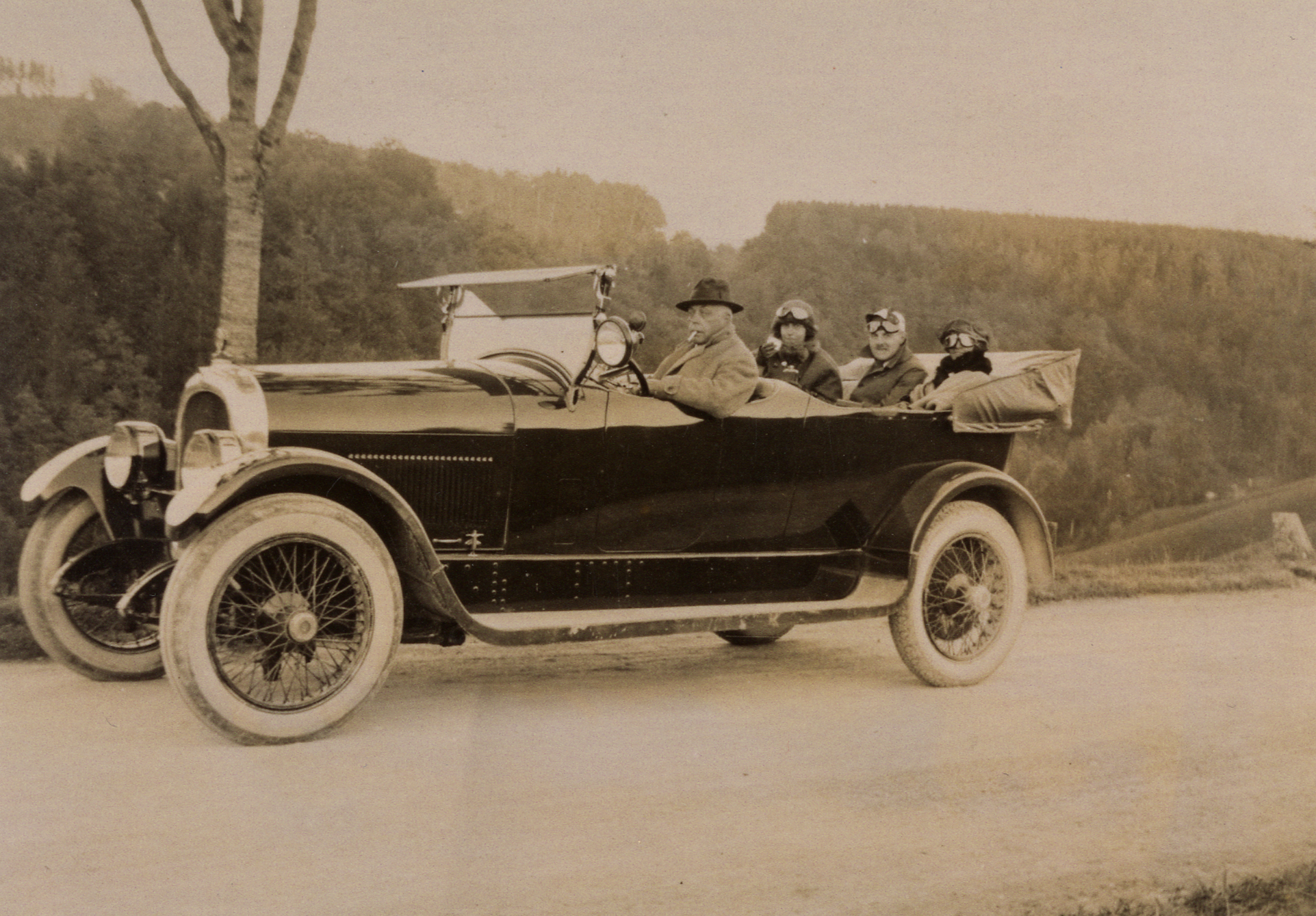

The Heuer family was also interested in

technical developments beyond watchmaking. Charles-Auguste Heuer was one of

Switzerland's pioneer motorists. Jack Heuer recalls:

“My

grandfather was really the grand seigneur of the whole family, and he became

one of the first people to drive a car. He had the fourth car in the canton of

Bern. That must have been around 1905.

It was one of those cars where you sat on the front and you had a sort of a steering stick which moved to the left or the right”. Heuer became a familiar sight, piloting his car with its tiller-like steering mechanism around early 20th-century Switzerland. He also became familiar with the many shortcomings of these early horseless carriages.

“Being one

of the first in Switzerland to have an auto-mobile he realised very quickly

that you never knew when you going to arrive because you had to stop frequently

to cool the engine and God knows what.”

In between dealing with an overheating engine, a punctured tyre, or a

slow-moving herd of cows on the road, it was easy to lose track of time. Heuer

wanted an idea of how long each car journey took him.”And so he invented what

we call the Time of Trip chronograph”. It was an invention that would make

Heuer the pre-eminent name in high-precision dashboard timing instruments for

rally drivers and motor racers.

Collectors of Heuer wristwatches sometimes describe the Autavia “as Heuer's first chronograph to have a model name, as the previous chronographs were identified only by their reference numbers”. However, the truth is that the Heuer family had been in the habit of naming different models long before 1960s.”We always had good names for the products”, says Jack today, recalling naming of such milestone timepieces as the Carrera, Monza and the Monaco. ”That's mostly learned from my father. He was very big on name-giving, dreaming about names and giving a product a name”. And, he, in turn, learnt from his father. As far back as 1890 the name La Sirene had been registered “followed by the Aligator, La Chimere, La Cigale and finally The Shamrock”.

At least as early as the last decade of the 19th century, the Heuers were in the habit of naming their most successful products, including chronographs. ”It was a real dashboard chronograph”, says Jack over a century later about his grandfather's motoring timepiece, ”and it was called Time of Trip. He used to sell that to the car companies, who would put it on their dashboards”.

The Time of Trip made its debut in 1911, and

used by everyone from postmen and soldiers to aviators, especially the

latter. ”The Heur Time of Trip clock was met with unparalleled success in

aviation and motor circles on account of its unique design, high-quality

movement, and sturdy construction”, explained the Company. ”In addition to the

ordinary dial there is a subsidiary dial. This letter is quite independent and

indicates separately from the large dial, and shows the duration of each flight

or trip in hours and minutes. When starting on a flight or a motor trip, the winding

button is pressed upwards, which starts the trip mechanism: at the same time a

little red disc appears in the small hole immediately opposite 9 o'clock on the

large dial. The appearance of this red disc indicates that the trip has

commenced to work. On completion of the flight or motor trip the trip is

stopped by again pressing the winding button, a white disc appearing in place

of then red one, showing that the record is finished. On pressing the winding

button a third time the trip hands return to zero ready for registering the

duration of the next flight or trip. This instrument is fitted with a flange to

enable it to be fitted flush into the instrument board. It is supplied in a

polished aluminium or black coated case and with either black or white dials as

many be required”.

When the Graf Zeppelin airship made its

round-the-world flight, it was fitted with a Time of Trip. Combining daring and

engineering innovation, this feat captured the imagination of many, including

Charles-Auguste's sons Charles-Edouard and Hubert, and it was out of the Time

of Trip that the first Autavia was born. As Jack recalls, ”My father and my

uncle became interested in a aviation before World War Two, and they started

saying ,”We have to combine this instrument both for the car and aeroplane :

they need this dashboard instruments”. So they created, I think it was my

father, the name Autavia. And then they built the dashboard stopwatch with a

twelve-hour register and minute register. They were not central, they were additional

small registers”.

It was those hard-to-read registers that

would indirectly be responsible for the birth of the Autavia Version 2.

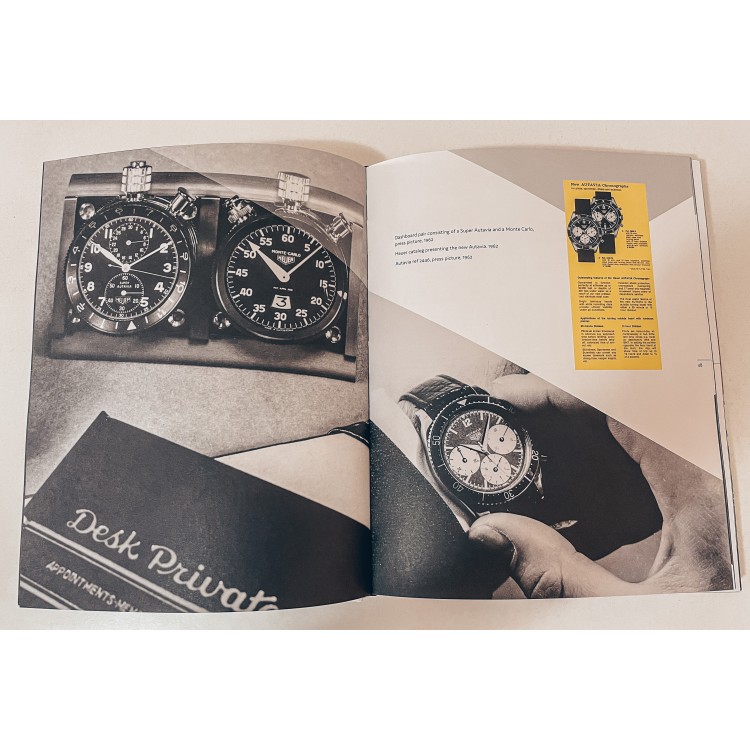

The Autavia was conceived as one of the

series of dashboard instruments made by Heuer and was most commonly paired with

a Hervue clock, a clock with an eight-day movement. Heuer instruments were the

choice of rally drivers and, by the middle of the century, anyone who aspired

to spirited sporty motoring has mounted a plate of Heuer timepieces on their

dashboard, including a young, recently graduated Jack Heuer, son of

Charles-Edouard.

“I finished my studies in engineering in 1957 and my father so proud that I was the family's first university graduate that he gave me a red MGA sportscar for my graduation. And so, having a competitive soul, I started participate in the regional car rallies with the son of our local garage owner in 1958”.

“I felt this

was a good way to show some of the dashboard instruments we made. So I made

myself a triple plate of dashboard instruments, including an Autavia, a

Mastertime, and one other. In the first rally, I was driving and my friend was

reading the map, but he wasn't good at map reading-I was much better because I

used to read maps on cross country runs. And, also, in the army you learn a lot

about how to read a map when you're an officer”. There is a strong military

tradition in the Heuer family-Jack's father commanded the last cavalry in

Switzerland, and rose to be a brigadier general. At the end of his own military

service Jack would retire with the rank of major.

“So the next time, when we entered our second rally, I was the navigator and he drove, and we came in very close to first place, we were third”. Jack could not have been angrier.”We came in third, exactly one minute late, because I had misread the small minute register dial. I was furious and called this Autavia dashboard stopwatch unusable rubbish and stopped production of the model at once”.

The dropping of the dashboard Autavia from

the product line left a hole in the range for rally drivers. It was soon

replaced by the Autorally, a 60-minute stopwatch that had a highly legible

central minute hand. However, still feeling the need for a twelve-hour timer,

Heuer approached movement maker Dubois-Depraz and requested an enhanced version of the 7700

stopwatch movement that would permit a

prominent digital display of elapsed hours that could be easily and

unambiguously read in speeding rally car.”A year later we added the MONTECARLO

12-hour stopwatch with a large digital window in the dial. The Monte Carlo

stopwatch became a must thereafter for all rally drivers around the world and

is still used in all vintage car rallies where electronic time measurement is

forbidden “.Such was its success that it was joined by other instruments

including the equally evocatively name Sebring.

“The old Autavia became redundant”, wrote Jack Heuer in his autobiography,“ and we withdrew it from our product line. However, we still had the excellent name of Autavia, which combined the words 'automobile' and 'aviation', available for a new product”. Jack was not a man who liked to see a good name lying idle and it gave him an idea.

“We were still a stopwatch company and not yet

a wristwatch company like now”, he says of the company at time he joined.

Indeed, the statistics regarding Heuer's stopwatch production are astonishing.

Even in 1971,over a decade after he joined the company, a decade during which

he had launched some of the most memorable and collectable sports watches of

the 1960s,Heuer was manufacturing around 330'000 mechanical stopwatches a year,

which accounted for around 2/3 of company turnover. This made the company, in

Jack's words,” the world's largest manufacturer of mechanical stopwatches”.

Almost as soon as he joined the company, Jack realised it was important to have the brand recognised for its wristwatches. “We had started making more chronographs again after the war”, he says. However, they conformed to an old-fashioned aesthetic, one that tried to minimise the size of the watch on the wrist and eschew an instrumental look in favour of a more sotto voce style. Jack was a young man in his 20s, and, what is more, an active young man: as well as running cross country and rally driving, he was a highly accomplished skier. He was also up to date with international tastes and in 1959 and 1960,spent a great deal of time in the US, creating awareness of the brand, building distribution, and establishing Heuer with such clients as members of the Sports Car Club of America.

He was in the New York on the evening of the 22nd of June 1961 when he opened a telegram from his father instructing him to return to Switzerland at once. Jack's Unkle Hubert wanted to sell the company.

Bleary-eyed and suffering from a new sort of tiredness and disorientation called jet-tag, he arrived at the Heuer offices in Switzerland the following afternoon and confronted his uncle. He suggested that instead of selling to Bulova, he would buy some of his uncle's shares, and taking the majority of the shares belonging to his father, assume control of the company. Incredibly, the older generation of Heuers agreed and within a couple of days Jack was “the majority shareholder in the 101-year-old family watchmaking business Ed. Heuer & Co”.

He was just 28 years old and in a hurry.

Immediately upon taking control, he decides that what the company needed was a new type wrist-worn chronograph.”I said, 'We have a free name so let's make a sporty chronograph with a turning bezel and a twelve-hour register”. Work began as soon as the traditional watchmaker’s holidays finished. “In the autumn of 1961, I decided to recreate Autavia as a wrist chronograph with my production team”.

At the beginning of the 1960s, Heuer's

wrist-worn chronographs were on the staid side of conservative, little changed,

in some cases, from pre-war models. With plain bezels, and monochrome dials,

there was nothing to set a Heuer chronograph from the dozens of competitor

brands. If this was a sports watch, it was worn by the spectator rather than

the sportsman.

Jack's vision was of a completely different

kind of watch: one that was recognisable at a glance; that captured something

of the vigour and excitement of rally driving or flying; that benefited from

the latest technology; that offered useful new functions to the wearer, and

most importantly, was easily legible under all conditions. Jack was going to

launch the modern chronograph for the modern man. The result would be one of

the most significant timepieces in the history of the company.

“There are two things that guide my design

taste. One is that analogue dials have to be legible for safety reasons, which

I learned at the university, polytechnic in Zurich. Because if you misread a dial in a power station it

could be a disaster. Everything was analogue in those years. In addition, I was

a fan of modern architecture by Saarinen Niemeyer”. As well as his mania for a

legible dials, he had imbibed the codes of modern desigh and become a huge fan

of Le Corbusier and Charles Eames'work as a student.

When launched, Autavia was a stunning departure for the brand. It was as if two decades of desigh evolution had been compressed into a couple of months.

Using the trusting Valjoux 72 hand-wound

movement, the new Autavia was a startling departure. In addition to the name

and rotating bezel, it was a large watch for its time, 39mm in diameter when

measured at the bezel. The stylish notches bezel with its 12 divisions catered

to the wearer who might jump on a jet plane at any moment, and fly halfway

around world-hence, the second timezone display on the watch. With the

exception of a sans-serif 12 under an inverted triangle of luminous material,

the hours were marked with simple luminous batons. Luminous straight-edged

dauphine hands seemed to float above the black dial, but most noticeable of all

was the trio of sub-dials at 3,6 and 9 o'clock. In contrasting white against

the black dial, they were so large that they filled the lower half of the dial.

They came so close to touching each other that they resembled three of the five

rings in the Olympic logo. It was bold, it was modern, it was stylish and it

was certainly highly legible.

“New Autavia Chronographs for pilots, sportsmen, divers and scientists”, trumped the first Autavia brochure. It was presented as a miracle-working wonder watch, its capabilities touted with breathless enthusiasm.

“Guaranteed to function perfectly at altitudes up to 35'

000 feet or depts of 330 feet under water as a result of our new pressurized

stainless steel case”...”Bright luminous hands with white recording dials

provide utmost visibility under all conditions”...”Incabloc shock protection,

unbreakable mainspring and a 17-jewel anti-magnetic movement ensure [sic] years

of dependable service”...”The most useful feature of the new Autavia is the

outside turning bezel with either a

60-minute or 12-hour division”.

This was deemed to be a novelty of such

significance that the brochure went on to suggest just a few of its uses:

60-minute Division

Pilots set known time marks in advance e.g.

approach time before landing, acceleration time before takeoff, estimated time

of arrival, etc.

Scuba

divers, Sportsmen and Scientists can preset any known time-mark such as diving

time, oxygen supply, etc.

12-hour Division

Pilots set time-of-day simultaneously in two different time zones e.g. local (or destination) time and GMT. In setting the pointer opposite the hour hand at the start, the ring will show time of trip up to 12 hours and down to 1/5th of a second.

Available

with two or three sub-dials, these were watches that reflected the spirit of

their times. Vestiges of Edwardian dashboard instruments and small chronographs

of the 1930s and 1940s with their barely legible, scale-crammed dials were

banished. These were modern watches for modern men; men of action who could fly

a plane as easily as drive a sports car; the sort of man who checked his

Autavia to see if it was time to go skindiving or skydiving.

There were also various strap and bracelet options: among them it is interesting to note that the watch was often presented on the distinctive double-grains-of-rice bracelet made by the prestigious Geneva chainiste Gay Freres, who made bracelets for Patek Philippe, Audemars Piguet and many others. Although it was a steel watch, Heuer was clearly positioning the Autavia as a premium product.